“I had a fantastic acrobatic double, played by Teresa Blake, and she opened the show by just holding onto the fringing at the bottom and flying up with the curtain, as if sort of lifting a veil on this space.”

Photos: Genevieve Cadieux, Hugo Glendinning, Daniel Faoro

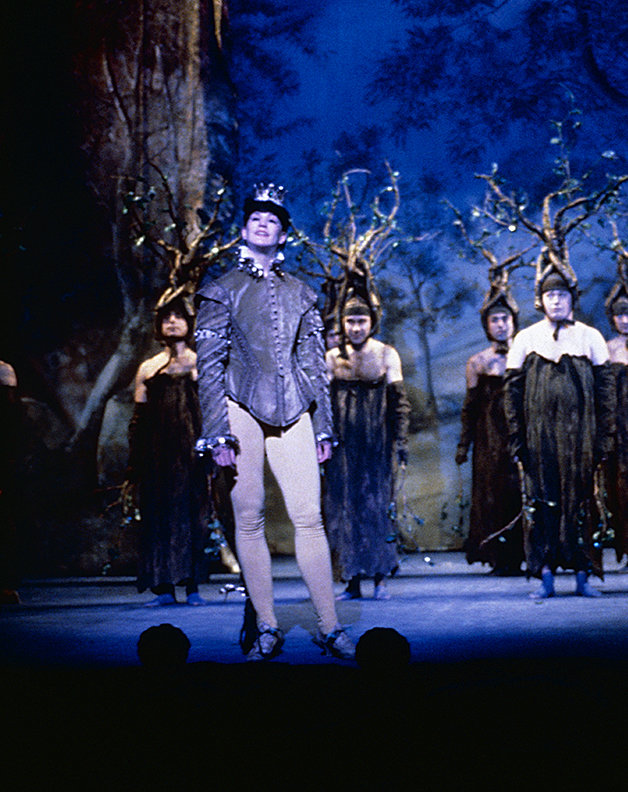

Rose English performs Plato's Chair (1983) | Photo: Genevieve Cadieux

A Trilogy of Works

By the final years of the 1980s, Rose English had become known for a style of improvised monologue she called 'abstract vaudeville'. What was said on stage changed from night to night, yet each performance emerged as a kind of metaphysical stand-up—a witty out-loud thinking that moved rapidly through long, loose chains of conceptual or musical associations; that lived off big ideas; and that played upon, anticipated and undermined an audience's expectations for a night at the theatre.

It began in 1981 when, invited to participate in an exhibition of feminist art at New York's Franklin Furnace, and ready to take a risk, Rose ad-libbed the hour-long solo Adventure or Revenge. Using a trunk full of costumes and props, wearing at times a false beard, she ranged over a field of inquiry that would become a lifelong fascination: the complex and often contradictory conventions of theatre, representation and fiction. Two years later, Plato's Chair deepened this investigation while brushing up against another enduring interest—that of the empty space, or the void, as a space of possibility and generative energy. Later, in 1987, the performance Moses broke two of theatre's well-known golden rules by taking the audience on a voyage through conceptual infinity in the company of two children (Dorothy and Harriet, aged five-and-a-half and nine) and one dog (Sam, aged four) who helped Rose explore the meaning of (mostly) everything.

Each of these performances, and a handful of others made through the 80s, had a different 'philosophical question' lying behind it. Taken as a set, they record an evolving interest in the turns of language, in the reflexivity of thought, in improvisation's energy and affordances, in the relationship between the word and the image, in suggestion and misdirection, in the traditions of entertainment, and in the idea of theatre as itself an 'arena' of thought (a guiding light through all of Rose's work).

"I would always refer to this thing called a script, which didn't in fact exist apart from perhaps a page of haiku-like notes." (40s)

As the 1980s drew to a close, the work shifted to a larger scale and opened to two new lines of interest. One reflected Rose's blossoming 'love affair' with the proscenium arch stage—a venue that allowed the production of spectacular effects (scenery changes, flying, skilful entrances and exits by wings and trapdoors) while at the same time framing these devices as explicit fictions and repetitions of a well-known theatrical language. The second big influence was Rose's contact with the circus scene in London at the time. Like the proscenium stage, the circus body opened the way for new, elaborate imagery while also being innately attuned to certain ideas of reality and representation:

I started to get interested in that strand of work by living in close proximity to two really important people—one was Sue Broadway, from Ra Ra Zoo, and the other was Jonathan Graham, who was one of the founders of Circus Space. I used to go and see their work and chat to them and became very intrigued by that sort of calibre of work, and by that extraordinary thing about circus where actually a moment when someone is doing something extraordinarily physical lasts a nanosecond but takes years and years to get to—it is literally a heightened moment.

The two preoccupations came together in 1988 with Walks on Water, the first of what would become a trilogy of pieces for proscenium stages. In contrast to the earlier monologues, which were comparatively simple and portable, Walks on Water featured a company of 28, twelve of whom formed a lively, all-male Greek chorus that both participated in the stage action and choreographed its scenic pictures (by wearing small saplings on their heads to form the forest of Act II, for instance, or stripping to trunks to become synchronised swimmers for the watery finale). Harnessing the capabilities of the Hackney Empire, on whose veteran proscenium stage the piece was performed, Walks on Water also incorporated three complete changes of scenery, climaxing with the revelation of a real waterfall designed by a young Simon Vincenzi. Rose, reprising somewhat the character of her early monologues, extended her own capacities through the use of an 'invincible' stunt double (Teresa Blake, of Circus Oz) who did the hard work of diving through fiery hoops, performing acrobatic tumbling, and unleashing gigantic flown jetes.

Walks on Water may have considerably upped the stakes in terms of pageantry, colour and immense costumes (Rose began the show draped in a red velvet cloak that trailed across the entire breadth of the stage, and ended it in a showgirl outfit accessorised with elbow-length gloves and a vast canary-yellow headdress), but it was still driven by an underlying big idea: in this case the question of whether infallibility, or even any kind of realistic certainty or solid belief, was possible. 'In the beginning was the word and the word was... doubt,' says Rose at the opening. Such expressions of disbelief may have been lightly delivered, but, as Guy Brett points out in his monograph for the book Abstract Vaudeville: The Work of Rose English, they also became 'politically acute in the era of Thatcherite intransigence'. In its joyous fullness Walks on Water was a kind of rebuttal to the prevailing spirit of the time, as well as, in a more positive light, a sly and seductive invitation to another mode of life.

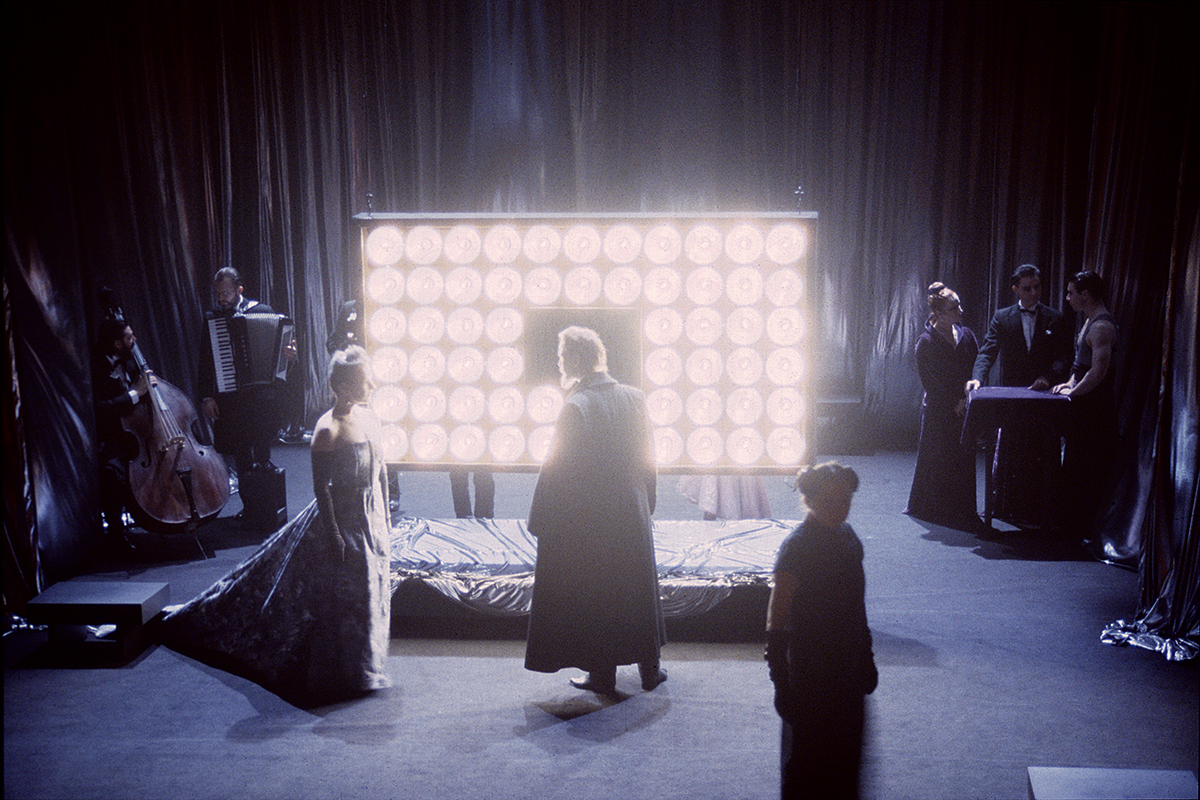

The Double Wedding, staged three years later in 1991, grappled again with our contradictory ability to believe in fiction by turning its action around the half-forgotten memory of a legendary performance (The Double Wedding itself), of which the cast cannot agree the medium (film, play or act?) let alone the contents. It was a show that meditated once more on the void, drawing some of its conceptual and design inspiration from research into the natural forces that reach across empty space, at both the microcosmic and macrocosmic scales. Guy Brett describes the set in Abstract Vaudeville:

The design, by Simon Vincenzi, renders the stage as a metaphor of deep space within the familiar terms and materials of theatre — drapes, platforms, stairs, exits and entrances. The whole is covered in black sequins to give the sensation of darkness and light simultaneously. [...] In the centre of the stage is a space concealed by the 'vortex curtain' running on a spiral track, which is thrown open at points during the show to reveal people and things, as in a nucleic core. This effect was the result of English and Vincenzi's research into diverse manifestations of the vortex, from astronomical and meteorological phenomena to currents of water.

Literally darker than Walks on Water, The Double Wedding also struck a more complex tone. Slipping into a silver dress and chillier persona, Rose appeared as the Hostess, a stalking presence who would both chide and encourage. (In an interview for Abstract Vaudevile, Simon Vincenzi remembers that she was the only character in the show to improvise: 'there was a genuine sense of fear amongst the other performers because that character of the Hostess was quite steely'.) The Double Wedding was also notably more ambitious in its script, staging and formal structures. A show with many moving parts, brought together in a series of comic and finally ecstatic meetings, it ended with the Hostess' extraordinary and tender address on the void and the vacuum, delivered from the centre of the ice rink:

and I asked

what is the difference between a void and a vacuum?and I answered the one is only empty

the other is a deficit of emptinessthe one is open and infinite

the other is hermetic and closed

it's a difficult package to tie up

it's an even more dangerous package to leave untied.

Given all of this, perhaps it's not so strange that the final piece of the proscenium trilogy, Tantamount Esperance, was staged as a conversation between five immortals about the nature of the soul. Yet Esperance again brought a marked change of timbre. It was neither improvised nor particularly dialogic; the characters in fact barely talked to one another, speaking instead into empty space as though the other entities on stage were only figments of a memory. The writing had a secretive density, almost a ponderous or monumental quality. Much of the script was written as verse and there were virtually no stage directions. (Those that do exist may challenge anyone attempting to restage the work: 'Espiritu weaves herself like a wraith around / Imogen's name holding its two parts together / by sheer metaphysics alone'.)

In some ways, it was the end of the road. Rose later called Tantamount an 'elegy' for a way of working, and the peculiar ephemerality of its atmosphere was matched by its own conditions as an artwork: though it took three years in all to create, it was performed only a handful of times before slipping into the archive.

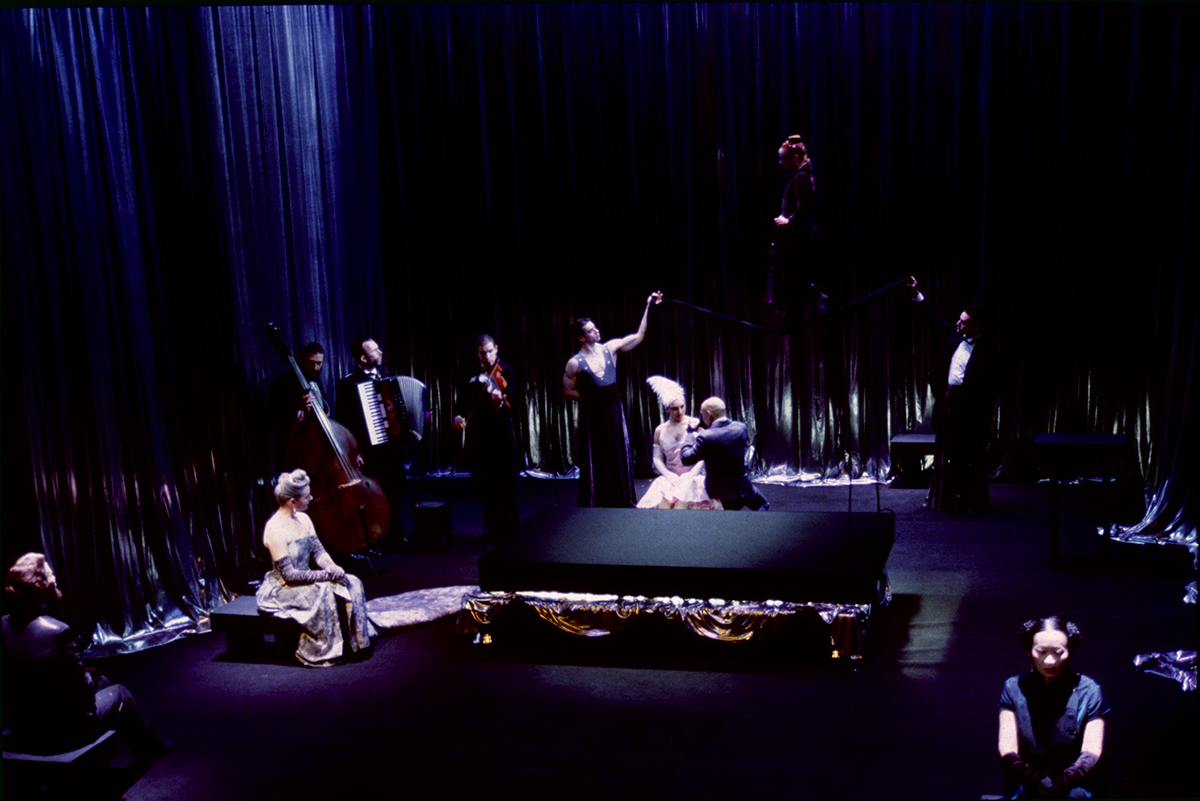

Another night passes in Tantamount Esperance | Photo: Daniel Faoro

The Entities

Near the start of Tantamount Esperance the magician Tantamount, standing facing the audience, delivers a long speech on our 'inability to embrace an idea of the future'.

What has happened to our sense of eternity? That

infinite future stretching in front of us? We

cannot see it because we have forgotten the past

and are not even noticing the present. It's like

being in the middle of learning a language and you

have no tense apart from the present. You cannot

communicate anything that you've done or anything

that you might do. It's all so erratic. You need

a sense of space from in front and from behind

you to be able to think.

'Millennium!' cries Tantamount, caught between fascination and frustration for an idea that has promised so much yet delivered only 'notoriety and the expectation of fever'. This sense of the Millennium as a failed project of imagination is the silver thread that connects the ethereal realm of Esperance to its political context and conditions of creation, and yet once evoked such direct appeals to the politics and cultural psychology of our world do not return. Instead, the millennial problems of Esperance collapse down to the realm of the stage and become embodied in the limitless possibility and ultimate ennui experienced by the four 'immortal' beings who orbit around Tantamount, the fifth.

These characters talk a lot, and do little. We meet them on the first night of their latest seance, scattered around a coolly-lit salon that bespeaks a space outside of time. Alongside the five immortals are several silent magicians and a discrete tango trio, occupying corners of the room.

The Set (1m 24s)

The personalities of Esperance are introduced in turn as their names are called. First, Espiritu La Verdad: dressed in a deep blue ankle-length cheongsam coat and wooden geta shoes, she expounds her philosophy while being lifted through the air, as though on a rising column of her own words. We see her moving in all directions: vertically up to disappear in the grid, in a diagonal line through cubic space, or walking horizontally, very softly and slowly, through a wide channel of blue light that crosses the empty air. Partly by virtue of her physical positioning, partly through the ethereal quality of her pronouncements ('viewed from above it looks as if I'm staring / into space. I am. but only in preparation for / understanding the nature of my quest'), Espiritu adopts the tone, if not the role, of narrator.

Next is Tantamount himself, a figure somewhere between a huckster, a grandiloquent out-of-touch school teacher, and a failed, forgotten god. He is the convenor of this meeting—the magnetic element that drew the others in—but if he is a leader and master then as we meet him his stature is diminished. His greatest feats lie in the past, and in fact he seems to be entering a small existential crisis, or at least some twilight of regret, as he laments: 'I've forgotten what tawdry means / possibly because I've become it'.

After Tantamount comes Imogen Grave, wearing opera gloves and a mottled grey stone-like dress that drags behind her. She enters the performance in a state of taut anxiety which we learn is both a degradation of some earlier state of peace and a symptom of her troubled relationship with Tantamount: 'the tango violins quiver. they are tender and / brutal and when I hear them I remember Tantamount / and what he taught me...'

Finally, there's the tango duo of Epitome Plaisir ('my nature is self-evident in my name') and Vanitas Splendide, who runs his hand over the dome of his bald head as through brushing back waves of black hair. Arm in arm, Epitome and Vanitas are the twin figures of sensual and social pleasure. Imogen describes them as they dance:

... Epitome always

sends her eyes on first. They are ineffable and

they languish, opalescent and burning as Vanitas

glides by, gravity hanging heavy in the air around

him, held in place by his personal magnetism.

Why are any of them here? Ostensibly the immortals have come together to have a 'conversation' about the nature of the soul, but perhaps it's truer to say that they embody different angles on this central question—that they are entities formed of abstract ideas. Vanitas describes the 'different ethics' of the group, and Tantamount and Espiritu pass back and forth the idea that 'The template for your soul is in the sound of your name'.

As one might guess, the problem of having figures who manifest different (and sometimes opposing) ideas is that their conflicts risk being irresolvable—like the mythological images of two gods locked in struggle. And indeed when we meet them the immortals are in a kind of stalemate. After declaring at the start that he doesn't want to 'sink into nostalgia so early in the evening', Tantamount immediately sinks deeply into it, the others swiftly follow, and we watch as they struggle to escape the past and articulate a 'secret' which lies half-forgotten—something that seems to separate them from a sense of certainty or simplicity to which they are unable to return.

Both is and is not

One uniting feature of Rose's work: a love of the contradiction. A good one is inexhaustible, a source of perpetual energy as the two opposite values spin around one another.

Esperance creates many, especially as the performance marks its final beats, but it returns most often to the concept of that which can and cannot be described, and to the desire to 'both withhold and reveal the secret'—which both does and does not exist, the paradox of which is itself the secret, if there is one.

Such formulations are common in Eastern philosophy and enshrined as logical constructions in the Indian tetralemma, also expressed as the concept of 'four corners' in Buddhist philosophy, which draws a set of four possibilities for any logical proposition: it is; it is not; it both is and is not; it neither is nor is not. As the image of 'corners' suggests, the goal is not a competition of discrete elements but a marking of the vast conceptual field that lies between them, and the tetralemma occurs most frequently in texts that tackle the insoluble or the unknowable: subjects such as the nature of reality and being, Śūnyatā (emptiness/voidness), and consciousness.

In Tantamount Esperance the contradictions and paradoxes scattered through the text are not only curios or games of language but expose breaking points in the matrix of what we understand. As with previous works, the language of Esperance is poetic, wrong-footing, tightly wound, and finally somewhat flirtatious in its promise of something that it refuses to name, and yet the old subversive playfulness is complicated and offset by its embodiment in Tantamount, who appears to have followed his intelligence to a dead end. 'Does everything have to be this dull?' he calls. 'Does everything have to be this miraculous and dull?'.

In fact, one could reasonably ask what are the benefits of immortality here: clearly these immortals are ageing and obsessed over its effects—Tantamount declares himself 'old and struggling' and 'all dusty around the lapels'; Imogen turns overnight 'from raven-haired to grey-haired'. They meet to share magic tricks which are both splendid and empty. And the silvered salon, for all its cultured civility, is haunted by the possibility that the price of immortality is an infertile loneliness. The five have the 'comfort of each other's company' but perhaps only for the scant pleasure of nine nights every thousand years.

Scrutiny falls on the layers of Tantamount's own identity as the others become progressively more disillusioned with Tantamount the leader, the magician, the keeper of secrets. Among the different ethics of the group, he seems to have fallen to what might be thought of as the Alan Watts approach: there is no self, so you might as well fake a good one. The result is impressive yet perhaps disappointing on closer scrutiny.

VANITAS:Finally he is on mock trial, standing 'at the terminus between body and soul', on the stage's central dais with its upper slab hovering weightlessly overhead. The others pace around as he restates his position: 'if the secret is that there is no secret then / this is the secret we must keep!'.

Tantamount's mind was immense but hopelessly

adrift. He constructed thoughts in lineal

filaments, woven like a birds nest but unsupported

by a structure and therefore left suspended in

space, incapable of incubating any progeny.

Esperance resists being read as a story, yet the closest thing it has to a traditional dramatic arc is Imogen's development as she moves out of the shadow of Tantamount's influence. We learn that she was not always Imogen Grave: that Tantamount found her floating in space—in some protean state, 'totally content'—before he named her and took her on as a discipline in magic. It is the name, though, that torments her, and the articulations of language more broadly. When she remembers that she 'longed for the soul to be invoked rather than spoken about' the sentiment both crosses the difficulty of art in touching metaphysical ideas, and captures the romantic desire to be swept into something larger that echoed inside the hopes and disappointments of the Millennium. The implication of Esperance is that it is time to shed the rigidity and absolutism of the past, an idea manifested by Imogen as she finally cuts free of the long train of her dress, reveals her subtle body, and exclaims for the 'archaic ambiguity of my name'.

there is no graven imagethe word conjures up the image

the image conjures up the wordthey are not in opposition

representation is both futile and heroic

everything can represent itself

but the object needs an advocate

it cannot argueif it is not noticed

If one can detect a tone of compassionate resolution in this, made blurry and ungraspable by stubborn conceptual irresolution, then that is appropriate. The text is deliberately slippery, right to the last, and the artwork itself takes on the aspects of an illusion: ideas flourish and disappear too quickly to catch; symmetries of language imply the edges of a larger structure; a delicate intimation arises which total knowledge could only destroy.

In the aftermath there is no position of power, no truth teller; nor are there any free wins for irony. Esperance distrusts centralisation and consolidation—of both meaning and identity—while its minor themes of loss of control, and the dangerous or destabilising effects of language (in spite, paradoxically, of its claim to bring shape) echo the threads of various creation myths.

Perhaps what finally stands is the tone or ambience that accretes around the work. Or perhaps its full meaning replicates in miniature with every paradox or twist of language—each of which leaves you unsure whether the dense pronouncement you just heard is the portal to a greater truth or a revolving door that returns you to exactly the place you started, dizzier than before. And of course there's a lingering sense, appropriate to all of this, that it might be both those things at the same time.

Conversation Notes

Rose English was interviewed 9 October 2015 at her studio in Bromley-by-Bow, London. A few quotes are also taken from a previous interview conducted in June 2010 for Crying Out Loud.

Commentary on Tantamount Esperance is drawn from two videos of the performance housed at the British Library (in the Sound and Moving Image Catalogue), and is additionally heavily influenced by Guy Brett's excellent monograph in Abstract Vaudeville: The Work of Rose English, which is required reading for anyone intrigued by Esperance or Rose's other work. The performance played 24 May - 4 June 1994 at the Royal Court Theatre in London, then 23-25 June 1994 at Manchester's Contact Theatre.

For the last ten years Rose has been working on Lost in Music, an ambitious project involving twenty members of Shanghai Acrobatics Troupe, glass objects modelled after the vessels of traditional Chinese acrobatic performance, and an hour-long composition and libretto for ten voices and one percussionist. The most recent output of the project was A Premonition of the Act, an installation/exhibition at Camden Arts Centre.

Related Materials

Abstract Vaudeville: The Work of Rose English, published by Ridinghouse and crisply designed by Sarah Schrauwen