So. How's it going?

It's great, it's fantastic. We have sold-out houses [for Inside Out], very good reviews—all of them except one that was the worst we ever had.

Has Inside Out been getting a different reaction to your other shows then?

Yes, it's always different—the shows you are creating are always having different language or different things to communicate. And I think with this one it's in so many layers that you could see just like a silly simple children's story, but it's up to you because there's so many layers that you could read the show through. We have a very easy story that you can follow and some people get stuck on that and other people are seeing other layers. It seems like the show is catching people. I think that the most different thing with this show is we get lots of long letters from audience members, saying that it has moved something in their life, and that's a little shocking but we're also very happy for it because it's sort of what you want when you are performing. You want to communicate and to add something to life.

Do the layers you're talking about come from collaborative practice?

Yes, in one way, but it's also that behind the performance there's a research project that's been going on for many years—both with scientists, about how the human body works and where is the soul in the body, but also I've worked a lot with circus artists, artists that are in Inside Out but also other artists, to find out what is the knowledge that they have about taking risks and balancing and dealing with the physical risk that they always have. But also with the mental... with the life situation in one way. A lot of circus artists, they prefer to have a moving life all over the world instead of having a house and a safe, secure living. And also a lot of circus history has been worked in—so a lot of the stories or the characters in the show have flavours from historical artists or stories. One of the artists involved in the creation had grown up in a circus family and in that circus they had an old grandfather. From the beginning he was the star of the show, but now he was old and couldn't get in any money for the show anymore and he was living in the truck. And he was totally fine. He had actually been the one who was the star of the circus before and now he was living there.

How did it work with the scientists? Did you workshop with them?

It started a long time ago; this is the second performance in a trilogy. The first one [99% Unknown] we worked on for two years—we had workshops with different medical scientists in the Karolinska Institutet, and it was meetings where we could ask questions and they could ask us questions, but then also it was workshops where we also tried out things, measured things, looked to see if you react differently if you are a circus artist rather than a normal artist. There were many levels to this collaboration; one was that we were interested to understand how the body works. It started when I met a brain scientist who had a lecture about how creativity works in the brain and he was saying exactly the things I had understood by working with physical artists. And then we started to talk about that—that my knowledge that I have from working physically only lets me think it might be like this whereas his knowledge from looking in a microscope—that's the truth. And what he was feeling was that it was only the factual truth—it's some truth, but when it's connected to the experience, the inside, you get the full picture. So then we started to work together. And then we wanted to know more things about cell division and other things in the body. They made it as a research project for themselves—so they have a research project and we have a research project, and we're interested in sort of the same things but from different perspectives.

And that was the first show. So it was a lot of inside the body and exploration—can you see a body as a microcosm of how the world is working? And then we asked all the scientists, But where is the soul? Can you describe where is the soul? And no one can describe it. I started to read all the philosophers and a lot of people have been saying the soul is in the heart, and scientists have been saying there is no soul and it's just chemistry in the brain, and obviously when you hear someone sing a song you can hear the soul in their voice—then when someone else sings the same song you can't hear it. It's obvious, but it's interesting to work with obvious things for me. We can't give the answer, but I think what you can feel sometimes with the show is the soul, and that's why it's so nice that the audience are reacting so much to the show. So they write long letters and change things in their life.

Do you have any idea yet of what the third piece in the trilogy will be?

Of course I have a lot of ideas, but I think I work very intuitively, always researching, and I think what really interests me is not what's happening but what's happening in-between—if you do a physical act you see a physical act but what's interesting to me is what's happening in-between—the thing that you can't point out. And when you take risks, when you do something that is very difficult for you, that's a way to push that thing to happen—because then you need to be so concentrated and so much here and now that you can't pretend and do something else. And that's why I think circus is so important to me: because you see so much presence or consciousness—and of course an actor can do that and everyone is working from being in that moment, but in circus when you are doing the physical things you always have to be there. So it's to work with an artform where you always have to be there.

And that's what you explore in the next piece?

Yes, I have a longer research project which is Circus Breaking Boundaries in Art and Society, and it's me and researchers from other things. And in one way it's about a lot of things—it's a big, international project over three years—but if you take it down to what it's really about then it's about this moment when life gets bigger than the here and now.

Cirkör are a big name in contemporary circus, but you're moving in other circles as well. Where do you see yourself within the circus field?

I don't think I'm thinking about it at all—I do what I need to do because of my inner voice. Cirkör have done very different performances, and we've always challenged ourselves by trying different collaborations with different directors or different partners. My own background is from the theatre and that's maybe... it's hard for me to say this because next time I will maybe make a performance that is really only the circus skill, but I also have my heart in the theatre—in the dramatic theatre. And also when I sort of fell in love with contemporary circus it was both about the skill—how you can extend the room because you can use the roof and everything's possible—and about how they use material. Like a table's not a table. We call it anti-circus in Sweden. It's a circus mind, a way of looking upon life: nothing is how it seems to be, you shouldn't think you know how things are. There's always the possibility to change it.

And if you look at our creations within the big field of contemporary circus, ours are a little more theatrical. And also this show we are performing on a lot of theatre stages; we're not only in the field of contemporary circus because when we tour we're booked by dance venues, theatre venues. And that I sort of like—because we are making the circus come into other areas as an artform. Not just circus, it's more like a piece of art.

I think I read that the first circus you saw was in Paris?

I was working in theatre and I was very happy because I had the opportunity to work with the most interesting director in Sweden and so I thought that was my life. But then I went to Paris—I went to work with Mnouchkine in Theatre du Soleil—and I was living in this house with circus artists and I followed them to their training space—and when I came into that space it was like here [Circus Space] but much more rough and outside. Then I was feeling that I'd found what I was searching for my entire life without knowing it existed. I started to see contemporary circus shows, and it was like I found my place on Earth and everything was possible, and it also felt like this was what we needed in Sweden because we were very good in text-based theatre, but what I wanted was to give the audience a kick in performance. In most theatres it's the same kind of audience every time—ladies around 50 mostly—and a similar show every month. It's not putting any marks into their lives. And that was what I felt when I saw contemporary circus in France: when the audiences went out from the shows they were walking a little bit above the floor.

So then I wanted everyone else in Sweden to have the same experience I had in Paris so I started Cirkör. So it was just because I wanted everyone to have the same experience. It's still like that.

What's form does your role as artistic director take in the creation of Cirkör shows?

It's been very different because I've not directed so many performances myself. Actually the only ones I have directed myself are this one and the first in the trilogy. Otherwise I have always worked with other directors or choreographers or whoever. And of course I have a lot of input, but it's also been my education. I had no directing experience before I started Cirkör. So it's also a way of learning. And what has happened during the time is I've felt more and more that I need to do it my way. So then I started to direct myself and I think that I'm quite confused when I direct because for me it's very very important to have it come out of the artists that I work with—so it's important that I work with this artist and not someone else, but its also that before I start to work with an artist I need to have a question for them—or I want to see this person open up in that way, or I want to have a challenge for them. I think what is always important, both in the directing work and in the creative process, is that what I want to give to the audience is that they go out of the show and feel they want to do something more. About their life or whatever. And we need the same feeling when we create the show—that we will challenge ourselves to go further in the creative process. So it's a challenge for all the artists and for me and we are not taking the safe way, putting on acts that I know are good. I mean I'm really good at making events—I know how to do them. But when I create a performance it's different; I hate to have the pressure that it needs to be a success and I need to play down that pressure. I'm working with the next piece now, and they've already begun to sell the show, and I feel like, How can you sell the show, we don't know if it will be crap. Because I need to do it as a journey—the creative process needs to be a journey with an unknown result. What I hope is that, when we work, the artists and myself find out new things, and new things develop.

So one way is I'm very interested in the artist—who they are and what they can be. But then I'm also very prepared before I start; so I have a lot of ideas before, both visual ideas and things I want to tell. In one way I have the entire play in my head and I could start to say, Go three steps there and do that—but then in another way I want to start from scratch with the artists who are there. But you never know how it will work.

I've been told that Cirkör shows change a lot, night to night, as they're being performed, and I was wondering what sort of form those changes take?

You work to the premiere and then for me that's not the end—it's just when we start to have an audience. And then we continue to develop the show because you always see things that could be better. When we had the premiere for Inside Out it was half of the show. I felt like we'd reached just half of the way; there's always more. And then when you have injuries and take in a new person—

I heard that your lead was out for a while.

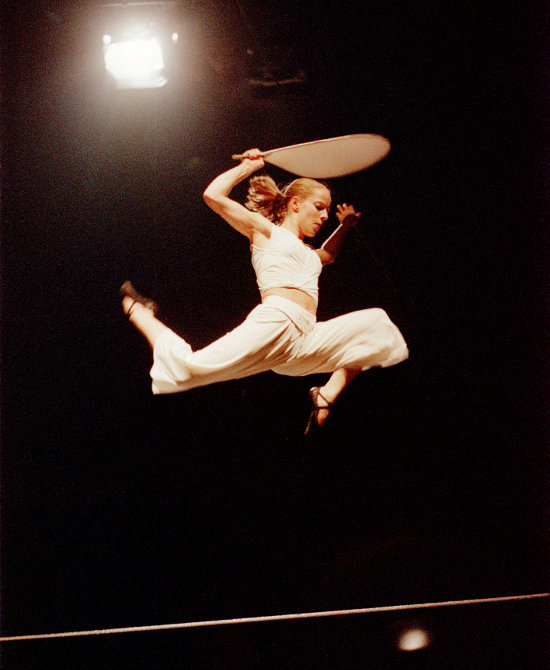

I changed her with a new acrobat. The replacement was Molly Saudek, who was actually a wire-walker, but I needed to work with someone who was—I don't know how to say this, but someone who had the right spirit for it, and that of course changed the story because in one way it's about taking the jump and this was like jumping on the wire, but with its balance and fragility... and it was actually in one way scary and perfect and fantastic or whatever to bring her in because after the injury with Anna [Lagerkvist] we were all so shaken because we had worked with the theme of risk all through... saying that risk was something good, but maybe we were a bit too tough.

One thing we haven't mentioned which is obviously crucial to the show is the involvement of Irya's Playground. Have you worked with them before?

No, because they are very new. But Irya, the lead singer, she was with us from the start; we've worked together for many years. She had a band called Urga and one of our most successful shows, Trix, was done with them. And then when I started to do this one I was thinking of her because I was thinking a lot of this question, Where is the soul? And she always popped up with her voice, because her voice—hearing it I've always felt that she has the soul. So we started to talk about it but then I knew she'd started Irya's Playground and I knew that it would be a very difficult process if we took them because then they'd want to perform their music and maybe not follow what's happening in the performance. So deciding to take her and Irya's Playground was a big risk—that we would be against each other rather than working together. And it has been very, very hard in one way but very, very fun and very interesting because some of the things that you thought would never work worked perfectly... and still there are some places in the show where I feel they are fighting about being the lead part.

Cirkör have a very extensive education programme and I was interested in what the relationship was between that and the artistic side. Is there much crossover?

Yes, no, we have a problem now. And that's that the training space is for the education—it's like here [Circus Space] I think—and we have actually no space to create. It's like a small black box, 100 square metres, where we are the boss. The circus school and everything else—the education programme, they are the boss. We started the black box to make a stand to make sure that the artists had a space, and now the next step is to grow—to have space where the creation is Number 1. But of course in the space where the education happens there is also open training. So professionals can train, but there's no place where they can leave the set and have quiet and focus and rehearse. But we are in a new phase in Sweden—we started the new training programme, and we have one high school and we have a university-level programme. And before the uni programme it was three years but with no accreditation. You can say in one way that Inside Out is also a reaction from that process because when we came in under the dance university we thought now everything would be smooth and we had lots of money—but then we understood that they thought that they'd just have another dance programme and they tried to teach the course as another dance programme. But it was so obvious that we are so different; you need to look at circus not only in the way of the training but also how you produce or tour or dream—we are not dancers.

So I think that's one reason why Inside Out is so circus. But now it's better. We had a lot of fights in the beginning and fights are terrible, hard, but it also means they've started to be interested in the new artform and see the differences. So now, since three months ago, the university isn't a Dance University—it's a Dance and Circus University.