In the rivalry between the Zoological Society in London and the Jardin des Plantes in Paris it was all about getting an African elephant. The Asian species had already been trapped and brought to Europe, and the sketchy understanding of the time preferred the African elephant as larger, perhaps much larger, than its near cousin. To have one would be a great symbol of power and prestige, and so it was a coup when the Jardin bought the first African elephant to have set foot in Europe in the modern age, an unimpressive runt who would later come to be called Jumbo. Jumbo however was not a crowd-pleaser, shy and ill-tempered, and when the Jardin acquired two more African elephants Abraham Bartlett, the superintendent at the Regent's Park Zoological Gardens, took the chance to bring in Jumbo in exchange for an Indian rhino, two young dingoes, a black-backed jackal, a pair of wedge-tailed eagles, a possum and a kangaroo.

At the Zoological Gardens, Jumbo sheds his shy character and becomes more gregarious (eventually carrying children on rides), but suffers terrible mood swings, making such thorough and concerted attempts to dismantle his temporary housing that he's eventually relocated to a larger, dedicated elephant house (which he also, gamely, tries to demolish). His keeper at the zoo is Matthew Scott, an antisocial, obsessive, difficult man who tends to Jumbo to the exclusion of all else. By their constant contact the two form such a strong bond that it seems Scott is the only one who can control the elephant, and as he begins to use this to his own advantage a long power struggle begins with Bartlett, one of those formidable Victorian figures blazing authority and discipline and will. The superintendent eventually concludes that it will be better to be rid of both Scott and the animal, but by this time Jumbo has become by far the most popular attraction at the zoo – a particular favourite of the children.

Bartlett's chance comes when Jumbo goes into musth and becomes uncontrollable, wrecking immense structural damage to his elephant house each night (though during the day he sanguinely continues to carry the zoo's children on the wooden seating he wears on his back). He is deemed a liability and sold to The Barnum and Bailey Greatest Show on Earth, but when the news that Jumbo is to be shipped to America circulates there's a public outcry at the zoo, with hysteric and angry crowds, letters to the superintendent from betrayed children, even a lawsuit. Behind the scenes P.T. Barnum stirs and aggravates, delighted with the publicity and the opportunity to announce Jumbo in the US as a priceless treasure stolen from England. He gets his way, and Jumbo, along with Scott, heads out for a new career in the circus...

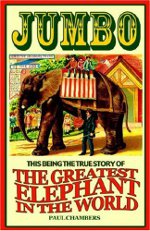

Paul Chambers' Jumbo is a short biography that tells the story of the world's most famous elephant (who was later of course Disnified as Dumbo). It's a tightly written book, adroitly researched, with Chambers applying a certain amount of scepticism and guesswork to pull a story from the ragged paper-trail left by Scott (who wrote a short cash-in memoir that described events as seen through the warping lens of his own self-regard) and Barnum himself, for whom the truth was ever a grey-faded ghost against the colour and vibrancy of his own inventions. As always with these things, without being an expert it's hard to tell how much of the book is interpretation and characterisation, but Jumbo isn't an academic text and it seems to have a real love for its subject and story. Jumbo is vividly realised as a complex animal capable of kindness, care and companionship as well as great violence and the stormiest moods. Scott is a dissimulating, unpleasant man, but is treated with sympathy; Bartlett can likewise be hard and cold, though his capability and foresight are admired. Barnum is made out, not unattractively, to be a sort of fearless marketing trickster god. When he discovers that animals imported to the US are exempted from import tax if they are brought 'for the good of the United States through an intention to improve the native stock' he pseudonymously writes an article bemoaning the US' reliance on other nations for its elephants: 'We now depend on the Old World for our supply of those noble animals. Were we to be engaged in a war with all the rest of the world lasting, say, a hundred years, we should become absolutely destitute of elephants, and the misery that would result therefrom would be appalling. What would our children do without elephants to amuse them? What would the sick do without the sight of elephants to invigorate them? What would the Nation do when the loathsome press of Europe would sneer at us as an elephantless people? To be truly patriotic we must rid ourselves of this abject dependence on other nations for our elephants.' As Jumbo tours America, Barnum decrees that no one may measure the elephant's exact height, speaking only of his great stature and constant incredible growth, with the result that, by the press' estimation, Jumbo grows about a foot year-on-year, taking on a mythic aura until, in St Thomas, Ontario, a dreadful accident collapses everything.

In the end, Jumbo's a lovely little book – in hardback compact and slim, printed on good paper, sort of the shape and size of perhaps a volume of collected poems, illustrated sparely with sketches and posters and the odd daguerreotype. And for all that it's short, it's long enough, big enough, that you might just be touched and saddened when you read of Jumbo's eventual fate.