Amid the bustle of Festival Circa, Compagnie 111 director Aurélien Bory talks to John Ellingsworth about new work Geometrie de Caoutchouc, science fiction and the posthuman, mathematics and art, the attraction of circus, and bodies becoming space.

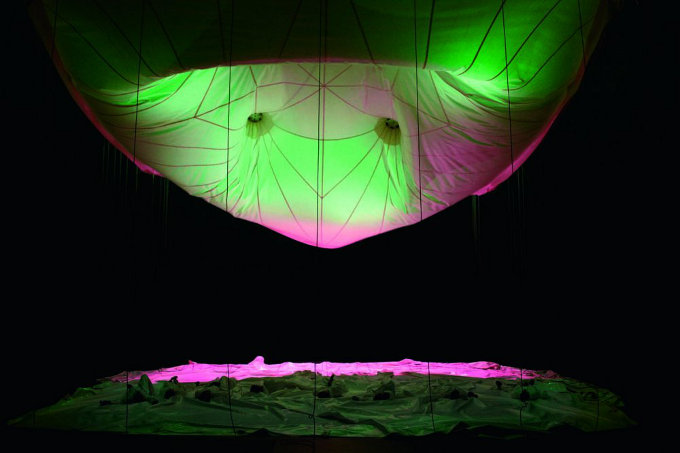

Inside the vast dark tent is another tent, a one-third replica, lit from within by green, suffusing light. From four sides the audience watch it, the miniature, as figures press the material out — silhouettes the shape of a man, a woman, a bird, swimming up and drifting down. It takes them some time to emerge from their shelter; and when they do, they do so slowly. The motionless head and shoulders of a woman glide silently out from under the hem of the tent, as though on a conveyor, then retract. Others follow, climbing fully into open air. They are new humans, moving like young birds navigating a slope on foot, ungainly and unaware, as yet, of their inborn capacity. Their movement is rapid and halting, their bodies still in factory condition, flexible and unworn. They meet in ones and twos at the edges of the tent and then, with much trouble, climb the slick curves to stand atop it. With nowhere to go, they turn their attention to the material beneath their feet...

The director Aurélien Bory has been making work with circus artists for a little over a decade now — mostly under the aegis of the company he founded with acrobat Olivier Alenda in 2000, Compagnie 111 — and yet Géométrie de caoutchouc, his latest piece, is the first to be performed inside a circus tent. Technically, at times, it’s performed inside two tents, with the audience watching and surrounding, on rectangular banks of seating placed on four sides, a scaled-down replica of the venue they occupy. As a feat of matryoshkan set design, the staging gives a first indication of Géométrie’s intention to situate itself in a disruptive relationship with the traditional idea of the chapiteau as an icon of circus, but then Bory is not, and has never been, a traditional circus director.

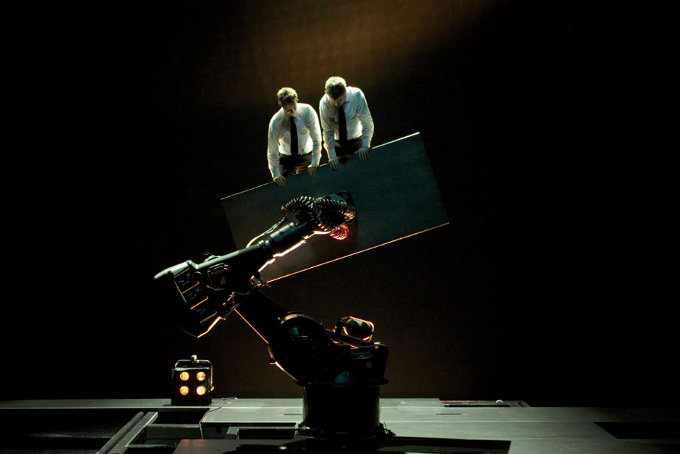

Since the foundation of Compagnie 111 and debut piece IJK — an acoustic and spatial extrapolation of the fundamental aspects of juggling — Aurélien Bory has made a name for himself with a series of large-scale works that explore the properties of materials and spaces to create a kind of living scenography or architectural puppetry: in Les sept planches de la ruse fourteen Chinese acrobats animated a moveable set of geometric shapes inspired by the Tangram; in Sans Objet the stage was dominated by a towering industrial robot arm (formerly part of a factory-line that assembled cars); and in Taoub, his collaboration with the Moroccan collective Groupe acrobatique de Tanger, the changing set formed and reformed from a single sheet of fabric. In Géométrie de caoutchouc, which premiered at Le Grand T in Nantes before heading to Auch and Festival Circa, it is the tent itself that comes to life: once the performers have emerged from inside the replica, the ropes tying it down are disengaged and the canvas flies up like a genie or rushing god, billowing and settling high above. Its face, squarish and pale, not unlike the face of a colossal heavenly owl, is animated by two metal discs with a transfixing gaze.

Thinking of this moment of startling animation, I first ask Bory, when I meet him at Circa, what the creative impetus was behind Géométrie de caoutchouc. Was he working with the tent as a rich, historic symbol, or simply with the physical properties of its material — the ways it moves, reacts, rests? ‘It was part of my interest to take an architectural space that is very well-known,’ answers Bory, ‘and to make it so that very soon there is not this idea of the tent as a symbol, but just the idea of the space itself and the relationship between the actors and the space. I’m very much more accustomed to theatre spaces, but in all my shows I try to start with questions about the space. I take the stage as very important and think about that, and all my work is around space: theatre seen as the art of space. Sometimes I am asked, Where is the humanity in your pieces? And I say I try to put humanity in the space — the architectures in Les sept planches de la ruse are alive; the space in Géométrie is a kind of... something. At the beginning it is more or less static, but it becomes more and more alive; it moves. And the actors themselves, I like it when sometimes the actors are less alive — they are alive but, for example when they slide very slowly down the fabric of the tent, they are less alive; they are like objects becoming part of space. They are not human beings anymore, they are just little pieces of space. So I try to make space more human and to make humans more like space.’

The performers in Géométrie de caoutchouc are not always inert, but they do act passively — or allow the space to lead them. Once the new humans are out in the open we see them draw together and form a sort of proto-society, becoming like a broken memory of a working group, cooperating to perform actions which its members don’t understand. When the tent is released the performers, eight of them, each take a rope and race and fall across the stage to pull the canvas down into a sail, looking tiny and confused as they scramble amid a chaos of ropes; later, with the tent held back at ground level, they run jerkily around its edge, appearing and disappearing behind billowing canvas that receives the image of mad shadows skitting along. Always there is something disconnected in their movement that suggests they are navigating from one impulse to the next, no thoughts beyond the present action.

In Géométrie perhaps it has found very pure expression, but all of Bory’s work begins from the idea of considering the space as itself an actor: ‘I try to work with materials that do something to the actors and to which the actors can do something. It is the actors themselves that push the elements together to build these architectures, but at the same time they are passive, doing what the space tells them to do.’ Is it the ability of the circus performer to flexibly occupy and respond to space that attracts Bory to the artform? ‘Most of my shows are with circus artists, and their background is in circus, but in my work it is with more of a theatrical conception. In terms of action or in terms of relationship to the audience there’s something theatrical and not something circus. What I tried with Géométrie was to take this space, this circus space, and try to push it toward the theatre.’

Working on the borders of theatre, circus and design, perhaps the unusual quality of Bory’s work lies in a desire to extrapolate the qualities of a circus artist and gift them to an object or a space — an idea that found its clearest expression in Les sept planches de la ruse, where a triangular block, balanced precariously on its point, had some of the same tension and simple drama as an artist holding a handstand. Bory nods at this: ‘It is the same drama. It is a mix between puppetry and circus. But if you think of circus artists, they are dealing with objects most of the time — even the acrobats because they have the trapeze. With the trapeze or the unicycle or the juggling ball what they are doing actually is just testing the possibilities of this object, and I think that space, in all of my shows, is a little bit like that. The actors have to find or experience a possibility of this space or object, and this is why I like to work with circus artists: a dancer is dealing more with the body itself or the body in relationship to the floor — the floor is very important in dance. For the circus artists, yes the body is a tool, but it is not really enough — what the circus artist is doing is experiencing the possibilities of the body in relationship to some simple or complex object, or with some simple or complex space. This is exactly why I’m making my shows with circus artists. Of course they are also puppeteers. They are trying to make alive something that isn’t alive; something that is just a rock or piece of wood. I feel really at the intersection of all these forms — circus, puppetry, theatre, dance.’

Working with circus artists and circus skills also comes naturally to Bory as a former performer. He hasn’t been onstage for a long time, but he trained as a juggler and performed in Compagnie 111’s IJK. ‘I feel close to circus artists,’ he says, ‘and in terms of process I’m exactly the same as when I used to be a juggler. I could say in fact that I am a juggler now, even though I’m not juggling. I think I haven’t changed — I’m interested in the same problems. You can think of Les sept planches de la ruse as a big juggling, balancing problem, and what I liked with that show, and what I didn’t expect, was the danger — we felt the danger of circus. With circus most of the time now we don’t feel this danger... I don’t know if it is a good or a bad feeling. I don’t know if I like it or not, but I know there is some danger in Les sept planches and I like the idea of danger — not real danger of course, but the idea that life is dangerous. Very much as you say in French mortelle.’

Mortality — and, more broadly, the nature of humanity — is something that seems to lie at the heart of Bory’s recent output. Sans Objet, particularly, was a striking science fiction fable that explored the idea of machine obsolescence as a metaphor to approach the question of what qualities make a human being a human being, interrogating the assumption that humanness can be identified by a checklist of physical characteristics. In Géométrie de caoutchouc, after the new humans have released the tent and explored the stage — explored the limits of their containment — they try to go back: bring the tent to earth and crawl back under the canvas, which, its energies dissipated, lies flat across the stage. They’re where they began, but clearly it’s not the same, and can’t ever be.

Whether Géométrie’s simple movement from order to chaos to void is read as a metaphor for the rise and decline of religious belief, an environmentalist parable, or a tiny enactment of the eventual heat death of our universe, the show is grappling with some of the big themes of science fiction. Is Bory conscious of this? ‘To me it’s funny because science fiction is not very easy with theatre,’ he says. ‘I think cinema or literature are fantastic for science fiction, but theatre... most often you see something very cheap; you can’t do big effects so you have to play with the idea. With Sans Objet the science fiction theme was very obvious because with these robots I wanted to talk about posthumanity and where it is that we’re going — but also about our past because technology is not from today. It is an old idea, technology, and I try to say in Sans Objet that technology has been part of humanity from the beginning, and humans and technology developed in parallel. Technology is now the dialogue of the everyday, and it will be more and more. Nothing can stop that. I didn’t want to say if it was good or it was bad — not at all — but to say that it is part of our world and it modifies our relationship to the world, how we live...’

In Géométrie, though, the technology isn’t at the centre of the discussion because there is no technology. ‘Instead there is this idea,’ says Bory. ‘What is the experience of living? What is the experience of living on Earth and in this universe? So there’s a universe at the beginning of the show, with the shadow puppetry, and at the end also when there’s this space. At these moments I see something physical connected to the universe; another person could see something else, but for me, in my imagination, it is something connected with physics, the universe, elements. What is the life and what is around the life? What is before the life and what is after the life? So this show is kind of first life and then the afterlife — a flat nothing which is like planets with no life, a desert. It is less of a science fiction show, but it is connected with another world because it is another world. It is a dream of another world which finally finished the same.’

But even though he has his own narrative interpretation, Bory is insistent that the work should be left open for the audience: ‘The show is experienced by an individual as a unique set of ideas, stories, references, and this is the real story — not the one I used to create the show. I used to say, “Yes, this is my understanding of the show”, but now I know that my understanding of the show is not more important than any other understanding. I want the imagination of each person to be very active during the performance, and this for me is very important: that a dialogue starts between the viewer and what’s happening on stage. This relationship is really for me the definition of art. Art is a relation; it is not the object itself. Only if there is a dialogue when this object is made, only if it makes me think something more, makes some connection, makes me think of this or that, makes me feel this or that. Because then we can say this is art because it is happening in our inside space. This is why I really care that there is space for slowness in my shows. I want to create some space for people to have time to choose their reason. I don’t want to rush things — which is also struggling a little bit against the circus concept, which is to rush things.’

One of the most unusual and obvious manifestations of Géométrie de caoutchouc’s slowness is that there are no unique actions — every movement is repeated. When the new humans slide down the fabric of the tent they do so over and over; when the tent is released and they pull on its ropes to draw it this way and that, every configuration is repeated four times, for the four sides. ‘It is at the same time something good and something bad,’ says Bory of this repetition, ‘because what I did is very logical. I followed a very mathematical structure. There is less life in that idea — it is an organised way of doing things. One time for each side; four sides, four times. So there is some mathematics here, but that’s not really why I wanted it: the repetition is more to embrace the whole thing and all the possibilities. Meaning life is a finite space; when you have experienced all that you can experience there is nothing else. And I really wanted to give that idea — that it is all that we can do; possibilities are not infinite. It’s a pity, it’s sad, but it’s true. And the older we get the fewer and fewer possibilities there are; so this is more at the end of the show. At the beginning of the show you have the sense anything could happen, that everything could happen. When they’re at the top it is chaos, it is possibility, it is people, many people, everything. At the end there are very few possibilities, so it is sad. They don’t have a lot of possibilities or choice anymore, so they just do what the space asks them to do.’

Matching the at times austere dramaturgy, the piece has an unusual score — sparse, solo piano composed by Alain Kremski. ‘It was a very odd proposition to bring this composer to a circus tent,’ says Bory, ‘because of course a piano solo is not music for a tent. But I had this intuition to have a solo piano, and I was pleased to find that this intuition really worked in the space. His music tells us something about the space, even the acoustic of the tent; we really use the acoustic of the tent. We don’t know where this music comes from — it comes from everywhere. You cannot say where the speakers are. I struggle with that all the time. I don’t know where to put speakers in order not to hear them, to not hear the origin of the sound, but in this tent you don’t know the origin of the sound. And this piano works very much in this composition about space... We also had some noise from the stage — all the noise that we hear in this performance is live; it is the sound of the tent, of the set. I used the acoustics of the tent because inside the little tent what you hear is incredible; we just put four microphones inside to produce all these fantastic sounds. So it was a good combination of beautiful piano — very simple, very economic, very slow, but very beautiful — and these sounds that are also very beautiful but in a different way, closer to the idea of chaos or accident.’

In light of these decisions — the repetitive structure, the slowness, the unusual music, the big, diffuse ideas — I’m curious whether Bory feels that Géométrie was a difficult or a risky show, and ask him as well whether it represents a change in his way of working. ‘Géométrie is my tenth show,’ he says, ‘so I have more confidence now to try some very difficult things. My problem in my previous shows was to seduce: I had to seduce the audience in my first shows because I was very frightened to disappoint people. And of course with that mindset, consciously or not, you put some limit on the work. Always in my work it was this combination with humour; I like very much humour, and in my previous shows there was a lot of humour to balance a little bit the reports that I had from the audience in slower moments or when it came to some more visual element. And I really like this mix, but... I did that.’

‘For Géométrie I wanted more. I had to say, OK, do something. Do the thing that you really feel, not considering if this person or that person will be disappointed or not. To be more courageous. And what happened to help me was I had some partners, co-producers, and the Fondation BNP Paribas helped me a lot, so there were all these people putting money in and giving me time to work hard on this project. And I said, OK, now the only rule I have to listen to is the rule of art. To try to make something the most sincere, and the most deep, the deepest I can. To try to make something important. And not to say that it is good — because I don’t want to say that. But to say I have to be the servant of art — more and more to be this servant. It gave me more courage to face criticism or people’s disappointment. And this kind of art you can have in some places of course, but putting it under a tent in front of 700-800 people... it was very dangerous, but I really wanted to experience that.’

‘Each night in Circa there are people walking out before the end. I have no problem with that. I know that it will happen. But I like this situation, and for me it makes some sense that some people are going out after 20 minutes and other people really take this show on their soul forever. It is a big contrast — art is made for that I think. I like humour, but there is no humour in that show. It is not what the work needed.’

Géométrie de caoutchouc premiered at Le Grand T, in Nantes, 11 October 2011, and was at Festival Circa 24-28 October 2011. The piece is currently touring, with its next scheduled performances in France at the Cirque Théâtre Elbeuf 13-15 April 2011.

In 2013 Compagnie 111 will present a new collaboration with the Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger in Marseille as part of the city’s year as a European Capital of Culture.

John Ellingsworth interviewed Aurélien Bory at Festival Circa 25 and 27 October 2011 next to the Radio Circa studio/booth at the Maison du Festival (part I) and sitting in the unseasonably warm sun outside key-promoter hive Café Sol (part II).