In earthy, poetic, surprising, asymmetric prose, John Fox, co-founder of Welfare State International, gives his own history of the company famous for their outdoor, community and participative work. It's written not as a factually exhaustive record, but as a dissecting exercise to reveal the inner workings of WSI's thirty year practice and to offer 'tools, models and lessons for the future'; where Engineers of the Imagination gives readers the hammer, the wrench and the withies of outdoor performance, Eyes on Stalks shines a light onto the ideas and attitudes that drove the work.

It starts in the late sixties with the company in Lancashire, inspired and charged up by peers like Bread and Puppet Theatre over in the US, creating interventionist art for smallish audiences – or sometimes for no one. Fox describes one ghostly parade at 7am in Barrowford on New Year's day, he and his partner Sue leading a white horse through the streets with their son Daniel, aged five, sitting astride it, a pair of 'big, real goose wings strapped to his back'. The company make installation work on rubbish heaps, organise processions described as 'foot patrols', and create work which, while maybe not always overtly political in presentation, is nonetheless powered by their sense of the duty of civic rage (in this sense, later, Thatcher is Welfare State International's great muse). They get a little attention, get a little funding, and start to work on a larger scale, producing gradually more complex spectacles which, as Fox relates them, seem like the wildest and most ridiculous fantasies. Here's a description of an event in Barrow, where the company settled for seven years in the eighties:

Around the top gutters of the town hall, firecrackers exploded to release four miles of pink and white streamers which at first hurtled down the sandstone walls and then billowed out in big bunches. Cables were strung between the two gable ends and the central clock tower so that the giants' bunting could be slowly pulled up in a triangle like a battleship dressed for the inspection of the fleet.

A large finger four metres long (Queen Victoria's), made with cloth and wadding, poked over the balcony and beckoned us all. Then her head appeared in the clock tower as she waved a giant lace handkerchief and our puppet Mayor waved back. This was the cue for simultaneous controlled mayhem. Massive daylight mortars exploded in the sky with puffs of crisp white smoke. Sam Samkin and David Clough were our fireworks experts again. 'It was like the Blitz,' people said later. I thought it was like a Turner painting.

Pouring from serried pots carefully placed on a hundred little platforms along the roof ridge, billowing red and blue smoke plumes (the town's colours) engulfed the whole architecture. An arc of lighted kites made by two Japanese kitemasters in residence with us (we had to stop them persuading children to trace Disney cartoons), made a rainbow a hundred metres long over the clock tower. Scores of church bells rang as planned. Ships' hooters blasted as planned. Shipyard alarms went off (not planned). Finally, as the rock band and every singer on hand sang a heavily amplified version of Stevie Wonder's 'Happy Birthday to Ya', the town hall clock went berserk, with the hands spinning round quite hysterically (there was a man inside). Then, majestically, in a McGill postcard climax, the Queen's bloomers rose up the flag pole, filling out with a sharp wind from the Irish sea. One hundred and sixty feet up, they looked quite small, but on the ground they were as big as a tennis court and had taken us three days of sewing.

There are quite a few of these rich and lunatic accounts. Another favourite is the story of WSI show The Wasteland and the Wagtail, a commissioned piece in Toga, Japan that ended up a cross between King Lear (a company favourite, it seems) and an Ainu myth about the wagtail. Starting with nothing more than a (less than ideal) location, the company find performance areas, find a subject, and build a rumbling, anarchic, night-long show that combines some of their mid-career trademarks: giant puppets, social dancing, and outdoor work alive to the advantages of weather and environment. It makes for an exciting chapter, but there are also lessons to be extracted for those with ambitions to make truly site-specific theatre, responding not just to geography and space but to history and social patterns.

It's also while in Japan that the company happens upon a lantern parade and are inspired to bring the tradition over to England (beginning a long line of WSI lantern parades and festivals). Fox describes it in some of the book's best writing:

High above us in a temple on the edge of a forested volcano, immense drums were being beaten. What looked like thirty tall stained-glass windows, each maybe four or five metres tall, processed slowly down a vertical track and swayed perilously through the trees. As they emerged, we saw that each float was carried by a turbulent wave of thirty muscular sweating men in white loincloths, accompanied by the drummers.

The lanterns themselves were made of shallow cloth or paper boxes, with candlelight, framed in carved mahogany and emblazoned with lurid painted demonic caricatures of gods and warriors. They were constructed as the sails of ancient ships rocking on the timbers below. It was a blessing for the fishing fleet and each giant lantern was surmounted with a small boy of no more than ten years old. He was strapped in as if on the yardarm or crow's nest of a galleon, which swayed terrifyingly. Each boat was placed on the sea and floated round the harbour until, in the distance, they became as tiny as glow-worms. As the primal drumming ceased we heard plaintive bells rung by the small boys on a leaden sea.

Following the big spectacles and fire shows, the company settles in Ulverston and begins the project to construct their own HQ, the Lanternhouse. It's an odd thing to read now, knowing that Arts Council England fully disinvested in the centre in its recent National Portfolio, and knowing too that it hasn't for some time been the base of WSI (who disbanded in 2006), but, again, there are simple lessons (and warnings) for any companies looking to entrench themselves in a building. As Eyes on Stalks draws to a close, it sees WSI's practice pulling back to work on Rites of Passage – using their skills to create events around weddings, namings, funerals and other pivotal moments. Remembering a funeral ceremony for a friend's partner Fox writes: 'Compared with such life-and-death disruptions of reality, theatre seems a hollow distraction. Even the most cathartic public theatre production could not emulate this one small private ceremony. After a decade of researching many practical models of theatrical invention I was asking whether most theatre work, including our own, was too generalised, unconnected and given to mainly enervating containment and gladitorial titillation.' John Fox and his partner Sue Gill continue their Rites of Passage work today under the name Dead Good Guides.

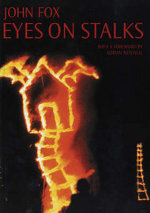

Eyes on Stalks is a book you must read – wise and committed and beautifully written. Not too misty eyed. The title comes from WSI's old slogan, 'Eyes on Stalks, Not Bums on Seats', and at the end of the introduction Fox gives his own kind of blessing: 'May your eyes wobble in their sockets, your creative juices boil over and your bum never ache.'