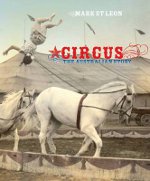

A ravishing, full-bodied, large-format publication on the history of Australian circus, Mark St Leon's book – or tome – is a minutely researched and even-handed account that begins with the Romans and their 'morally depraved venues of entertainment', heads into the less familiar ground of circus at medieval fairs, goes on to the 19th century and the appearance of circus in Australia following the deportation of bareback rider James Hunter (the 'Yorkshire phenomenon', shipped out to the colonies for stealing 'some bedding from furnished lodgings'), pushes on through the rise and fall of the wagon circus, the rise and fall of the rail circus, and the rise and fall of the motorised circus, and emerges finally in the last few decades to cover New Circus (the company and the genre), Circus Oz and the establishment of the National Institute of Circus Arts.

It's a book to pour over: the main text threads between photographs, illustrations and images of old posters. Definitely they have not skimped on these. As the book draws toward more recent times the photographs are probably going to be a little more familiar, but further back there are many fascinating items, including: a contract for grooms at the Eroni Bros' Monster Circus and Menagerie that binds new hires at the centre of a fine web of forbidden activities ('The nuisance of long-winded arguments in the dressing tent is forbidden, also smoking during performing hours. A fine of 4/- to 10/- to any person starting it.'); an excellent picture of a 13th Century female acrobat handbalancing on top of two swords at Bartholomew Fair, plus a good number of other colourful pre-daguerrotype drawings that are low on verisimilitude; a handwritten application to the Colonial Secretary in Hobart Town for a license to put on an equestrian display in an arena; the first known poster for an Australian circus show, and many subsequent broadsides begging most respectfully to inform the reader of such wonders as 'THE MOST BEAUTIFUL PONEY IN THE WORLD: SILVER KING'; an advertisement where famous wire-walker Con Colleano (who went to America and was successively billed as an Australian, Spanish and Mexican sensation) gives his endorsement to Wheaties breakfast cereal; and sundry other marvels.

The text, too, is full of passing mentions of fascinating fragments of anecdote and research. We learn that in Elizabethan times wandering acrobats were considered as bad as 'heretics, Jews, pagans and sorcerers', and that it wasn't until 1935 that travelling circus performers were 'differentiated in English law from the rogue and vagabond'; that in Signor Dalle Case's Foreign Gymnastic Company one of the attractions was the 'wonder dog' Munito, who 'translated any word from a list of 350 foreign words, selected and waved any national flag nominated by a spectator, and played dominoes with gentlemen in the audience'; that there used to be travelling bush boxing troupes who hiked around challenging locals to enter the ring and fight the champion (the book has a particularly evocative picture of this); and that there was a celebrated English clown whose stage name was Reuben Cousins but whose real name was John Plevy Bumpuss. We learn, as well, how the goldrush brought circus out of the cities – how people used to pay admission with gold dust and throw nuggets at the feet of popular equestrian riders – and we read about circus' part in the Eureka Stockade incident in 1854, when revolting diggers commandeered the Jones, Noble and Foley circus tent for storage of arms and ordered the circus band, at gunpoint, to play all day for miners building a makeshift fortress. We hear of the influx and effect of American circuses (probably best encapsulated by the small line in the corner of a Sells Brothers poster: 'The supreme test of merit is success.'), and of the great rivalry between Wirth's Circus and the FitzGerald Brothers in the early twentieth century. And we can read the story of Wirth's encounter with the 'bushranger' ('highwayman') Frederick Wordsworth Ward, aka Thunderbolt, aka King of the Forest, and a riveting, tragic letter from Ida St Leon to Rill Wirth Martin occasioned by the death of his brother.

Basically the book is itself like a collection, an archive, and the author its gentlemanly and modest curator. Divided into thematic sections (and with essay asides on subjects such as Australian circus language, a day in the life of a horsedrawn circus, poster advertising, clowns, etcetera) the chronology of events can be a little confusing, but there's a timeline in the back and it's meant anyway to be read slowly and with care. Written as a labour of love by Mark St Leon (who has his own connection to the Australian circus), and designed by Pfisterer + Freeman, it's a slow-release art object – one you'll surely hold onto.