Mental illness is vivid and also soulful. The soundtrack of mental illness is turntable scratching or bass-heavy dance music. Obsessive compulsive disorder manifests principally in outbreaks of pop n lock. Jumping off a building (onto a crashmat, with back layouts) may be the best cure for schizophrenia.

In spite of a clever introduction that blocks out portions of the audience in squares of light to represent psychiatric statistics (delivered in monotone by software), and in spite of the assurance that 'the recognition and understanding of mental disorders has changed over time', at the end of the day Psy's just not that interested—not in the reality of mental illness or the ethics of its representation, not in understanding, not in connecting, not in looking for the humour that gathers richly in any desperate situation; only in getting laughs and an easy frame from the regurgitation of all the standard cultural misperceptions. The cast are presented to us like a new range of Mr Men: Mr Paranoid, Mrs Agoraphobia, Mr O.C.D. (actually his given name in the programme, incidentally), Mr Mania, etcetera. This is broadly the extent of their characterisation, and you spend the show both trying to remember which disorder adheres to which character (is he Amnesia? what was she again?) and to see past an overlay that brings no vital insight, no contextual benefit.

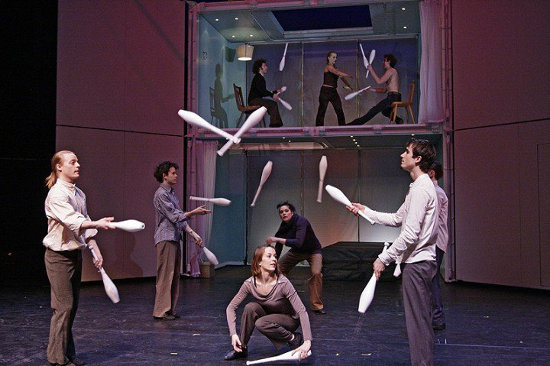

There are some good artists involved. Florent Lestage is a brilliant juggler and a fine stage presence (and the only member of the cast who even approaches a 3D character). His silver medal act from Cirque de Demain gets cut into Psy a little clumsily, but it's still powerful. Sitting on the psychiatrist's couch, an amnesiac, he starts to remember an event from his past, feels something, and the scene shifts to a park. Joggers and tramps and business men pass by oblivious, and Florent—a free agent or spirit among them, like a character moved back through time—slips the clubs they carry from under their arms, takes a coat, a newspaper, a crooked cane: what he needs. As he juggles the clubs—catching them in a balance on the arm of the walking stick, or lightly in the bed of its curve—music swells up. You're swept on its current, but captivated by Florent's skill and charm and his lightness as an acrobat, the way he controls his body with such apparent gentleness, and not by the connection, or the disjunction, between this state of grace and the manifestations of his disorder.

So it goes. You get a glimpse of something really alive, when a character is on a street and a stream of people walk through him, knocking him this way and that: circling round to come at him a second time, they pass beside him without touching him, but he twists and turns just the same. It's beautifully choreographed (some good flocking and deflocking if you're into that) and speaks eloquently of a state of mind where thought, anxiety and the contemplation of risk can have an immediate, physical effect. Along with Florent's routine, it's an early high point. There are other things to like about Psy—the abilities of handbalancer Naël Jammal; Guillaume Biron's trapeze routine (better I think without the information that he hears voices); the large, compact cuboid set that unfolds into a cross-sectioned house—but it doesn't come together, and by the second half the production has more or less abandoned internal consistency, the original conceit overrun by the need to hurry through and showcase the (admittedly high) skills of each member of the large cast.

Is it terrible? No. Is it enjoyable? Sometimes. Psy's concept isn't going to bother everybody—although I would suggest that you should be bothered, and that there are analogous situations of social insensitivity that an audience wouldn't stand for—and I'm sure it considers itself a light and quirky take on a serious issue. It would be easier to stomach that if not for the opening voiceover's statistical grounding (which is basically inviting the audience to reflect on their own experiences), and, similarly, if not for the end sequence, where the cast morph into psychiatrists and walk out to the edge of the stage to look out over the lighted audience, tilting their heads and making clipboard notes: perhaps the madness here is ours.