Like an exhibit in the storehouse of a museum, a dark bulk wrapped in black polythene. The light is low and there is no one to see – no one but us – as the shape beneath the plastic flexes, moving slowly. Cautiously it twists and opens, becomes larger, the sheet stretching to disguise its form. Turning on the spot, the thing explores the parameters of its movement. It is nothing human, yet there are aspects to recognise in its changing shape. At first you think you see a head, then it has a head. Unmistakeably it has a head. It grows very tall, and spreads itself wide, and seems like a cowled figure, like a vast Death, turning to look at you. And then, quietly, it folds down again, lights come on, and two men in suits enter to remove the covering. Underneath there's a machine arm: jointed complexly, very large, fed by thick, coiled wires. Pistons lie like muscles on its exterior.

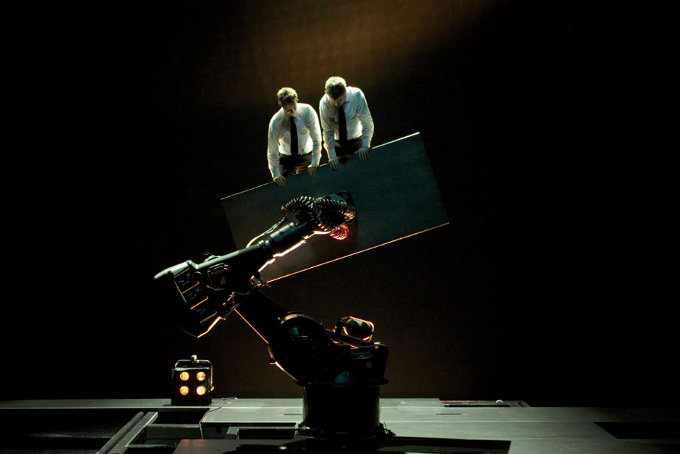

The arm unveiled, Sans Objet in fact starts lightly enough, the two men, Olivier Alenda and Olivier Boyer, enacting some neat stage trickery that erases the line between the organic and the robotic: Alenda becomes a boyish, junior cyborg as his head is seemingly replaced by the boxy cassette-like tip of the machine-arm; hanging from a plank of wood that the arm holds aloft, the bodies of the two acrobats are joined by the eye, so that the legs of one man and the head of the other become the end-points of a single, distended human, his snaking midsection hidden away. These sorts of perspective games are funny and very well executed – and, I suspect, typical of the director Aurélien Bory – but they make a space as well to quietly echo some of the thinking that lies under the piece and that is interested, really interested, in what physical conditions have to be met for a human being to be a human being – and in what might reasonably be subtracted, and whether our corporeal reality has anything to do with the abstract and ethical codes with which we define ourselves. In other words, whether a person is a set of ideas or a biological template. As the piece navigates this conceptual tangle, it moves beyond optical illusion. The two performers take on the clipped movements of toy robots and engage in rote tasks; the arm exhibits meanwhile a surprising range of dimensional articulation, mastering the entire sphere of its effective range, yet showing the greatest care when, for instance, it slides back a plank of the staging it rests on to locate, underneath, a floodlight-box pulled down to a warm, orange glow, lifting it delicately as though between two fingers.

Gradually machine obsolescence flows into human obsolescence, and the question of the future use of the machine's functionality – of how to reimagine it's hulking industriality – is answered in an extraordinary and provocative final scene. A sheet of dull black polythene is stretched out and up to obscure the entire stage, the same material that at the start covered the arm, but thinner-seeming now and taking shallow, rippling breaths. Suddenly, it is violently struck; there is a great noise, as of metal on metal, huge and deep. It is struck again, and again, the pounding becoming harder and faster, and then the polythene begins to be pierced, over and over, beams of light streaming through tiny rips. When it stops, the only sound is the moving arm, the lines of light now angling through the tears as it tilts and tracks on the other side. And then, with no noise at all, it cuts a door, and the two Oliviers step awkwardly out as men with cast heads, as new humans. They stand before the audience; they say nothing; they return through the cut portal.

Many people are going to read the end as dark or bleak or dystopian or frightening, but I don't think that can be everything that it intended, and the sum of the show is more subtle and intelligent than simply The Machines Will Crush Us, Rule Us. I've been reading fictive explorations of the ethics of machine intelligence practically my whole life, so I have a lot to invest, but watching a robotic arm dismantle its own work station so that it can use the planks of wood to build a sculpture of standing towers is, to me, an eloquent and peaceable revolutionary act. When the arm lifts one of the men, folded over on his stomach in a position of vulnerability, it does so with striking tenderness, and where it is disobedient or aggressive it is only disrupting the repetitive, fruitless – in other contexts we would easily say 'machine-like' – actions of the two men: throwing them forcibly from the box whose cramped interior they walk endlessly around as wall rotates to become floor, wall, ceiling, wall, floor.

Sans Objet is a great show, on (for theatre) an unusual subject, with many moments of astounding and unforgettable scenography. It reaches deep into the heart of puppetry and mime, and shows us again our innate and exact ability to read emotions and character into movement – even when that movement is pre-programmed and executed to within the nearest centimetre. In doing so, gently, it suggests that a future test of humanity will be to reject our longest and deepest held notions of what, in fact, constitutes humanity. It does not shy away from the difficulty of this, and the fear of this, but it demonstrates to us that it is not, not simply, man versus machine. Because it can only be a competition if the two sides remain distinct. And what would you say are the chances of that?