Blindscape takes place in near darkness, in underground caverns, across rooftops, beside waterfalls and under the ocean. The audience are free to move wherever they like, but are guided by sound queues delivered by smartphone as they search for light to reveal the performance happening around and among them. John Ellingsworth talks to the artist Skye Gellmann about glitch art, losing control, the character of light, and combining improvised physical performance with game design.

'First thing I do is I walk into the space naked and I climb up the pole in a spiralling way. In this first section I kind of become like a hologram or an image — because the audience are in a heightened state, and my image is lit by iPhone light, the scene becomes surreal. '

A show which moves through five levels, including a disco, and culminates in an improvised team-play competitive game, a show which sends each audience member on a privately mapped but collectively shared quest to find light and illuminate the performance around them, and a show which, in spite of its foundational use of technology, can't really exist on video — to hear Skye Gellmann tell it, Blindscape is surreal. Or unreal. Or maybe hyperreal? Realness itself is at stake.

At the start of the performance, outside the space, each audience member is given an iPhone with a set of headphones. Led through the backstage areas, they're taken into a dark, curtained off room adorned only with a central Chinese pole, and given their instructions through the headphones: during the performance they will have to find light. The iPhone tracks their location and orientation within a 3D soundscape, and signals their proximity to light using the sound of wind chimes: they grow louder as the audience member approaches light, quieter as they move away. When they find light the screen of the iPhone illuminates and can be used to reveal the physical environment and the performers who occupy it.

Blindscape Audio

Audio introduction to Blindscape (requires HTML5 compliant browser). Download as an MP3 here.

In this first section the two performers, Skye and co-deviser Kieran Law, slip in and out of the space and the language of the piece is, as Skye puts it, 'sculptural', the audience illuminating static or slow-moving images which, like sculptures, don't look back. Unlike sculptures, however, they might appear and disappear, looming in and out of Blindscape's darkness. 'Because the space is surrounded by curtains we can come in from any side,' says Skye. 'The space becomes... disorientating is the wrong word, but the space is designed so you lose track of where you came in.'

As the game progresses through a series of levels — five in all — the objective of finding light becomes steadily more challenging and the environments grow more complex, the simple tone sounds that make up the first level becoming full soundscapes that send audience members through underground caverns, over rooftops, behind waterfalls, into the interior of a train, and down to the ocean.

The idea to experience a landscape only through sound was the seed for Blindscape's long development: it's first iteration was actually as a short, conceptual computer game, developed by Skye with his friend Dylan Sale as an audio-only experience where the player navigated a series of soundscapes using only headphones and a keyboard. In 2005 they showed an early build of the game at the Freeplay Festival in Melbourne, where it was well received, but the project at that point was still just an idea, a concept, and eventually slipped out of mind. 'We didn't know exactly what to do with our cool idea,' says Skye. 'The project slowly died away, but the central idea kept brewing in my subconscious. For years I continued to make games alongside my circus work, then in early 2011 Next Wave Festival opened for applications. By that time I hadn’t done any game development for a year or two, and had the itch again. The old Blindscape idea found a new expression in the iPhone. Using the gyroscope we were able to make 3D soundscapes feel more real then ever: the player could turn their body in order to look around these landscapes in physical space. Blindscape was really just waiting for the right time.'

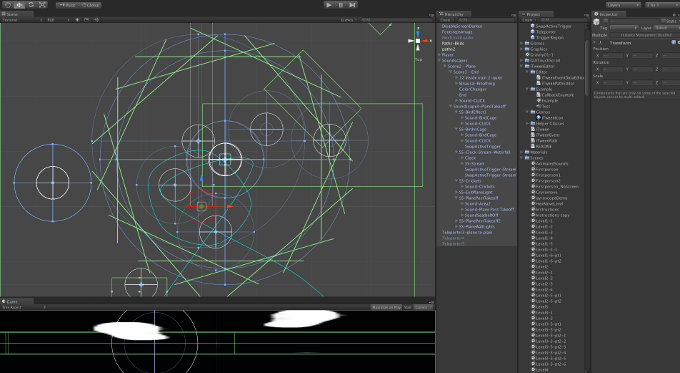

Screenshot of one of the Blindscape levels.

Blindscape's original programmer, Dylan Sale, returned to work on the app, physical theatre performer Kieran Law came in to co-devise and -perform the piece with Skye, and Thom Browning designed the soundscapes for the game. The piece premiered in May 2012 at Next Wave, a multidisciplinary, genreless festival, which, while not self-identifying as a live art event, shares a few of that form's enduring interests: durational work, secular ritual that investigates urban routine, the visceral body, disruptive technologies and their possibilities for sensory manipulation, and, most of all, artwork where the conceptual origin and framework is a critical and indivisible part of the whole (the performance being sort of better thought of as a manifestation of a larger and ongoing creative process).

The Next Wave programme might not seem like the most obvious home for a circus piece, but when I talk to her director Emily Sexton is clear on the place Blindscape earned: 'What bound Blindscape to the other works in the programme was its interest in the relationships between audience and performer,' she says, 'particularly in how that could be mediated by technology. Many artists in Next Wave are experimenting with their artform, stretching and pushing what is possible or "allowed". That culture of experimentation is unique, and we went to a lot of effort this year to ensure that people really did see it as a united collection of artists taking risks.'

Blindscape is the first of Skye's pieces to be programmed at Next Wave, but Sexton was familiar with his previous work — productions characterised by a stripped-down aesthetic centred on the performers' physicality, the use of non-conventional spaces (or the non-conventional use of conventional spaces), and, as Sexton articulates it, a sensitivity to light 'as a character in its own right in the work'. In the solo Retinal Damage, the performance was cut into slices by the mechanical light of a slide projector opening and closing; in Scattered Tacks, a show made with Terri Cat Silvertree and Alex Gellmann, high-powered flashlights and head torches were used to rough effect (Skye: 'that show was built in the squat so it had that kind of grimy squat feel'). In Blindscape, the light is, more than an expression of a particular aesthetic, a subtle yet affecting presence that is constantly both demanding its own attention and diverting that attention elsewhere. Sexton: 'You feel elated when you win light, frustrated when you don’t, and intrigued by the distinction between what the performer wants from you and what your own personal journey requires.'

Hearing Skye explain the dynamics of the piece, I'm curious about the experience of the performers — if it's a strange, split experience for the audience then what must it be like for the two of them, navigating a night garden of insulated audience members, seeing only by the diffuse light of upheld iPhones? 'It is surreal,' confirms Skye, 'being in a room full of people that are in their own little bubbles, and for the audience there's so much going on — they're problem solving and they're trying to work out where the light is. When me and Kieran come into the space we know exactly where everything is, but we can't hear anything. We've discovered that when people have headphones on it puts them in their own little world, but also makes them more open to suggestion.'

And while the show is built to be robust enough to survive the most stubbornly individualistic of audience responses ('even if an audience member decides to wander beyond the black curtains and go backstage the game still functions and the show goes on,' says Skye), it nonetheless makes it easier for the performers if the audience allow themselves to be immersed in the Blindscape world. For Skye and Kieran the show's technical execution means it's impossible to know exactly where the audience will be at most given moments. 'We can't predict where they'll find light, but we can predict when they'll find it,' explains Skye. 'There's a flow to the piece; generally one person finds light, then three, then five, then ten, then fifteen — and the whole room is filled with light.'

In game design this form of non-linearity is sometimes described as the parallel path model: player choice is permitted in discrete sections but is reigned in as the game passes through specific milestones, the possible paths, if you visualise it, curving outwards only to collapse back in at a series of points spaced along a line. In Blindscape this structure of fluctuating freedom and control underpins the show's driving interests in the nature of virtual and physical realities, the division and granularisation of attention, and the increasingly dominant role of technology as a mediator for our senses and experiences. 'There's this tension between the user controlling the show and the show controlling the users,' says Skye. 'So it begins very much that the audience has a lot of control, and then throughout the show we take that control away. It snowballs to the point where me and Kieran come to the space and we change the rules: we begin to directly interact with the audience.'

A desire to break the rules, the system, the game informed the development of Blindscape from its earliest stages. During the devising process Skye and Kieran picked up the term 'glitch art' from visual art practice as a nuanced descriptor for the style they felt they were discovering. 'It has to do with failure, but it's not failure,' says Skye. 'It's just a break in a system and from that break something else is born. You don't see the break as a failure.' Working on the physical material for Blindscape the two would push tricks or movements to breaking point, then go past the breaking point — an improvisation method that they are constantly running within performances of the show itself. Skye: 'The tricks are “glitched” and broken. Bodies fly and land dangerously, mangled in strange contortions on the floor. It becomes what I call “fragile acrobatics”, a term which actually came from a juggling friend of mine who described his juggling as fragile juggling because he'd gotten to the point where balls were flying everywhere and he was dropping a lot.'

This way of thinking and working connects Blindscape with Skye's earlier performances, but he sees the new piece as an evolution rather than a continuation — the same basic urge driven by a different, more refined and more exact intent. 'I've done a lot of corporate circus performance, and some of my work was kind of a rebellion against entertaining people. So with Scattered Tacks, the first show I made, I had this idea, What if I make a show that people hate? It's going to be the worst show, so shitty — and then it became really popular. In the other shows failure would be a part of the work, but it'd be me spinning on a bowling ball until I got really dizzy and fell over a lot. It was really blunt; in Blindscape it's doing this more gentle thing.'

'Blindscape is the show where I really want to go into darkness with the audience. There are long sections of the show which happen in complete darkness, including eight minutes of Chinese Pole where the audience can only see four minutes. First of all I like how the actions which happen in the dark trigger a reaction from the audience which forces them to look at things with an outside perspective. Then I like how, once they accept the reality of only seeing fragments, an intense focus is created. Through this we see the essence of the body — and at the same time question if the glimpses of circus we see are actually happening or are just imagined...'

Blindscape will tour venues in Australia early 2013, after which a European tour is planned.

For more on Skye Gellmann's work see his website.