Sideshow talks to Stockholm director Marie-Louise Masreliez about her piece What About Charlotte, made with three artists confronting the motives of their present and the facts of their past.

Pulled from the wall he is stuck to with silvery duct tape, a strip torn from over his mouth, Jonathan Priest begins What About Charlotte with a dreadful and compulsive joke about a Holocaust survivor who wins the lottery and is afterward driven to build a giant, golden Hitler statue. When the punchline comes the audience aren't sure, and Jonathan starts to explain that what appeals to him about this joke, this awful racist joke, is its structure, its essence – the way it pulls you in with the image of the towering Hitler, his hair and moustache cut from black onyx, his lips sculpted in red gold, his eyes taken by two fist-size sapphires – and, then, as well, the possible story that runs underneath the main current: what it might mean to build an idol to 'something that nearly destroyed you, but didn't, and made you stronger'.

What About Charlotte is a piece that has grown out of the personal stories of its three artists (Anja Duchko-Zuber, Jonathan Priest and Björn Olsson), stories that, as audience, you are not privy to the details of, but which you can sense have some measure of pain. The performers move as though on unpredictable, elliptical orbits, which at times cross or synchronise – they're in the same place, and traversing the same terrain, but from different directions and in different ways. You witness... something; a sort of ceremony of passage where something from the past, long ignored, perhaps unwelcome, is taken into the light.

What About Charlotte's director is Marie-Louise Masreliez, a Stockholm-based artist who was distracted from a rather more conventional university education and career (in pedagogics) when she fell into circus. After training and performing in Sweden she ended up at Carampa in Spain, spent a year there, then came back to Sweden and partnered with another aerialist to perform cradle. The duo were accepted into what is now the DOCH school, but, as Marie-Louise told me when we met up for an interview, her education was soon interrupted: 'After two years my back was injured – I got this fractured disc – but I was still interested in the stage and how to perform circus in different ways, and I thought the field hadn't been fully explored yet. I was really inspired as well by dance and movement, and it was then I decided to try to do the rest of the course as a director, to switch focus.' The school agreed, and Marie-Louise swapped technical work for classes with the choreographers, taking students from the course and artists from outside the school to make her first piece as a director and her final piece of the course, Psyccess.

For Psyccess and each new piece Marie-Louise works with the same process, which originally she called Psyccess but which has since changed its name to the more descriptive Motion Participatory Choreography (which I can't help thinking sounds very slightly like the name of a leftie intellectual hip-hop supergroup from maybe San Francisco). The core of the method (which shows the influence of Marie-Louise's mentor at DOCH, John-Paul Zaccarini) is Marie-Louise interviewing the artists she will be directing: 'I have questions I ask myself: what was driving me? Why did I do it? Why didn't I stop when it hurt? What was it that made me do all these things? And I want to pose these same questions to the artists, so already in the selection I choose artists who are interested in finding out more about themselves. We meet up for interviews, and every artist has a story about themselves. 'I always knew that I was a mover'... 'I could never sit still in school'... 'I just couldn't write, knew that I had to move' – and this story is not enough for me. I always try to go deeper and find what their motivation was. Often we come to a breakpoint, the moment where they took the decision to become a circus artist, and I try to make them remember that breakpoint and what was important for them at that point and how it has changed since.'

From there they take the answers into the studio, but the dialogue stays open throughout the research process, and that process is itself very open and changeable: the material from those first interviews is a start point without, at first, an intended direction or end. Perhaps in devising they will isolate and strengthen an emotion or memory that came from the original interviews, or use something there as a shape or template to grow something else, or, most loosely, take the material as an inspiration to suggest new ideas and connections.

At a certain, pre-set point the research is stopped, a script is written, and rehearsals / technical devising begin (with What About Charlotte these necessarily spread over a long period of time, with days here and there for single runthroughs and the artists working on their own material individually). At the same time, work begins with a small group of collaborators: for What About Charlotte, the composer Niklas Swanberg ('his view of music I think reminds me of my view of circus arts, because he talks about how to “fill the air” and he sees music as like layers of density that he can almost feel'), the lighting designer David Nachmann, and the costume designer Kerstin Ribers.

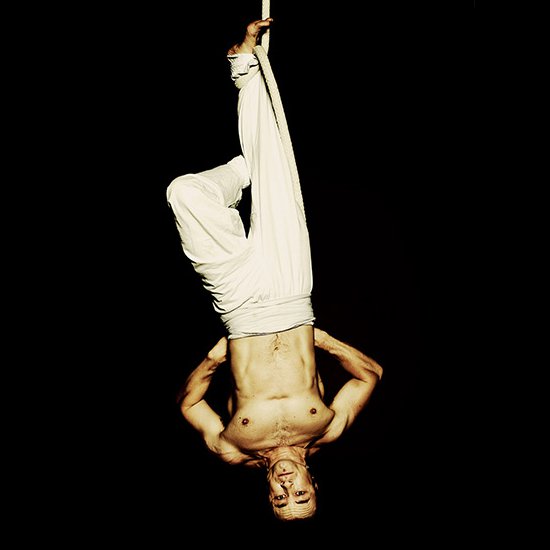

There's no set designer, and What About Charlotte is nothing more than a bare stage and a centrally located rope. 'When I started I felt I had seen so many shows with objects, with props,' says Marie-Louise. 'It's a common thing in Europe that you use a lot of props, and I felt that for me I can't handle that – I can't handle the objects because I want to focus on the people and what we can do with their relationships. For me that's more real than interacting with an object. There's the artist's relationship with the discipline, the space, the fact that there's an audience there – that's a lot of things for me to puzzle over. To be able to relate to other objects in a naturalistic way requires a kind of training that we don't get in circus school – this theatre training of how to be with an object.' It's an approach that's markedly different to the sorts of shows that are generally imported to the UK (with their giant robots and flying stages), and to the ambitions that those grand productions inculcate in young artists. 'It's almost everyone's dream at school – “I want to build a structure.” I've heard so many people say that and it's like, Yeah, but maybe you don't need it. It can be just the person because the person contains so much.'

In searching for performers who are willing to go deep in investigating their own motives and practice, Marie-Louise looks for artists with an individual approach, and finds this type more easily in circus than in dance. 'I prefer to work with circus artists because I find their skills more interesting, and I also think that traditionally a dancer comes from a school where you have to have a certain level of technique to be able to perform modern dance, ballet, classic. I consider circus different because it embraces individuality – you don't have to have a certain physicality to do circus; you have limits that you can overcome, and you don't have to erase them, you don't have to train them away. You can actually embrace the limitations of your body and make something different from it […] These circus artists interest me because they've found something that has great importance to them – almost everyone I work with made their discipline into their own discipline.'

Jonathan Priest has certainly made the rope his own: he's perhaps an unusual shape for corde lisse, bulkier and visibly more powerful than most, but with an organic, curling style that's entirely distinct. In What About Charlotte he circles the rope, comes back to it again and again, and it struck me as unusual to see aerial performance, on a regular apparatus, that wasn't contained within the single, momentous expenditure of an act – because aerial in theatre, however beautifully interpreted, however tonal or resonant, tends to keep its borders against the work around it. Here there are many short sequences, begun and broken off, that slide in and out of the wider movements of the piece; 'integrated' is a terrible word, and this time the wrong one, as the skills are the shape and substance of the piece. Marie-Louise: 'I want to show that there's something interesting in what we do, and it doesn't necessarily have to be tricks. The act of grabbing a rope is already telling something. Climbing a rope is telling something. And you can climb in a million different ways – if you just take your time and investigate that then you see things that you didn't see before. That's interesting for me, to just explore and show – and it's not constructed actually. It's not like I've said I have this act and then I'm going to put things around it. It's more like I have this story I want to tell – it has a beginning, a middle and an end, and, well, the rope fits here. So for example climbing the rope is Jonathan's job; that's what he does every day. And we had this thing where I wanted it to be that he leaves to go to do his job every day. And if you get the picture you can be like, Well, what kind of work is that? And that's exactly where it started, with Jonathan saying, Well, I have this job and it's to climb the rope every day. I go up, I go down. I go up, I go down.'

When I ask, Marie-Louise tells me that the Hitler joke, as well, emerged from the interviews: it was what Jonathan came out with when Marie-Lousie asked him to tell one. As it sits in What About Charlotte, it speaks to ideas of performance and sincerity, performance and power, the truth in fiction, and the weight of the past, but, as with everything else, it has no exact lines nor meaning: 'What I wanted to create was a story that made people laugh and then think about why did they laugh. It wasn't really funny was it? But this man telling the joke in this way made it feel funny at the time. I don't know. This was the idea. It doesn't matter if no one understands it, but if someone does that would mean something to me – that I could plant an idea in someone.'