Quidam was probably amazing once. A bored young girl is transported from her parents’ world into another place: a dreamland where she encounters strange and sometimes frightening characters, led all the while by a puckish guide who ultimately reunites her with her mother and father. It’s a basic and effective story, which by all accounts worked a decade ago, when the show was first premiered, because the cast were the people who had created the show – it showcased their technical abilities, but also suited their characters and traits as performers.

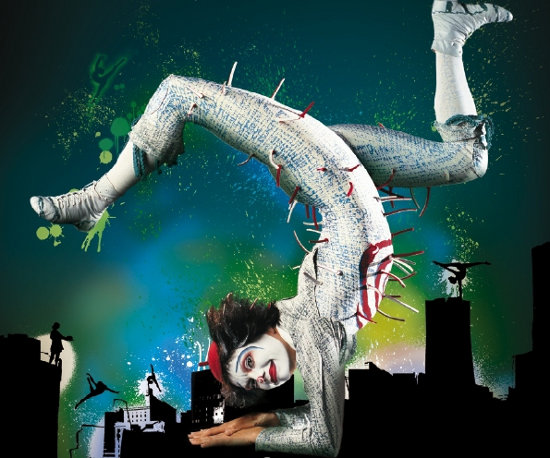

Over the years, though, performers have been swapped out and in, and replacements have been judged on their ability to pull off the tricks of their predecessor rather than chosen for their like spirit. You end up with performance that is impressive but empty: a silks aerialist with a huge back-bend; eerily fast Chinese diabolists; standard high level acrobalance where there is no sense (as there is a sense in good duos) that the movement and balances of base and flyer are the gestures of a dense, unique communication – privately arrived at, publically shared. There was a man-size female handbalancer who wore face make-up but showed nearly all of her bare tattooed skin and looked like a drag queen, so wildly out of place tonally that it was as though she had accidentally performed her late-night cabaret act.

From what I’ve heard it’s probably not so much that the performers don’t have character or individual style; more that CDS as it has become doesn’t consider the artists themselves the most important agents in the creation of work – giving them no input into the structure or final nature of the show. But there is not much evidence of a live directorial presence either, autocratic or otherwise. It’s perhaps the case that CDS has grown to the point where moneymaking is (in a sense automatically) the driving necessity, a situation in which the artist cannot take risks (because there is so much now to collapse if it ever went wrong). And if something is working financially, if it’s touring the world and getting good audiences, there’s no impetus to change it, even if theatrically it’s broken.

What makes it worse is that there’s one act, the last, that truly reaches and quickens the heart. It has a technical name that I don’t know how to spell, but it’s also called Baskets: three or four acrobats link hands and use their combined strength to toss a flyer fifteen-twenty feet in the air. In Quidam there are more than a dozen on stage, allowing the flyers to be tossed from one basket to another, crossing midair; the finale constructs a human tower, each flyer somersaulting onto the shoulders of the last. It’s terrifying and at times unbelievable, but there’s a basic drama in it that is deeper and subtler than the possibility of injury or death, or the thrill of watching people exercise the skills they have given their lives to attain. If you accept that part of what makes a group of people a community is mutual dependence and the attentiveness of its members to one another, then you find that operating here in its most extreme form. The acrobats literally owe each other their lives, countless times; perhaps this exists only in the moment and space of the performance, perhaps backstage they’re actions toward each other are motivated by the same small attractions, irritations and jealousies as floor-staff at a supermarket – but this doesn’t make it any less powerful or real. There are tiny pieces of choreography, performers clasping hands, moving in sequence, that amplify what is inherent in the act, and it could have been a perfect end to a great show. Maybe originally it was. The intention is still visible: to create a cast of dreamworld characters, then at the end to unite them in grace. It’s sad that the supporting material is no longer enough.