Plot: an angel falls from the sky into a sort of forest kingdom. He has lost his wings, and while trekking around to find them meets an insectile princess in a deep-green costume of spikes and ridges. They fall in love, but the princess is kidnapped by slender women with green hair who winch her into the ceiling and celebrate with a quadruples trapeze routine. Later, the princess emerges from a cocoon and is reborn as a high-level contortionist and handbalancer; she is reunited with her angel; they acquire headdresses and long gowns and are married at length.

It's fairly standard Cirque du Soleil, romantic and vague, with the characters talking in a burbling made-up language that sounds like a racially insensitive impression of an indeterminate nationality. The audience's ability to follow the narrative is probably further impaired by the decision to combine several plot-critical moments with the introduction of an entrancingly beautiful helium balloon—a sort of mini-zephyr with planes of intersecting light sweeping across its skin, projected from under its skin, which is walked on a tether around the stage, high above it, so the whole audience can look happily up while below the princess and angel go through the motions.

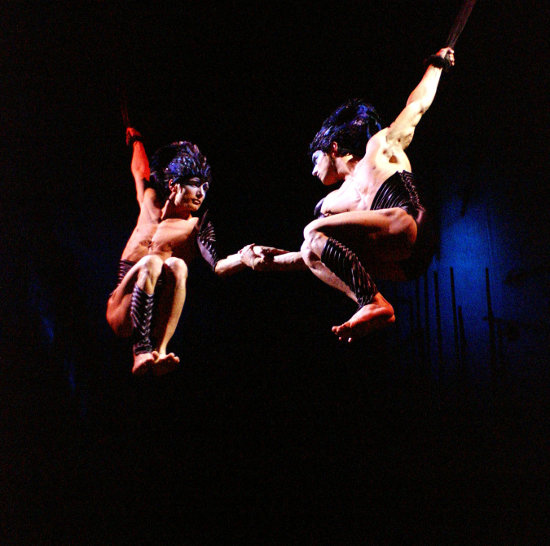

All the good stuff is up. Starting from within a forest of pole-trees, a seemingly freehanging scaffold staircase wends up to the ceiling where a central opening like a cathedral oculus is bathed in green light. It's from this aperture that our angel falls in the dramatically lit and genuinely captivating intro. His aerial hammock routine, too, was probably my favourite of the night—because it was great seeing the vocabularies of aerial loop, silks, and straps brought together in one routine; because there was so much height, combined with some neat counterbalance; because it was just about the only piece where the performer didn't wear a skin-tight bodysuit; and because Mark Halasi is just a very good aerialist, having lightness and fragility to offset the endlessly rehearsed confidence and strength.

With the plot sketched in the background, Varekai proceeds more or less like a typical Cirque du Soleil show, presenting the usual formula of acts which, on this occasion, includes some wildly swinging aerial hoop (making good use of the Royal Albert Hall's massive circular space); a fairly bizarre piece combining partner acrobatics and foot juggling which is hard and esoteric enough to make you laugh and shake your head (if you're not already laughing at the costumes: gold Lycra with cowboy-esque red flaming tongues at the arms); and a dance on crutches by Dergin Tokmak, whose sinuous upper body seems to move forward and back in a wave.

Also in the line-up are tiny Chinese boys in puffed-out graduated blue costumes coloured like blendable pencil demonstrations – they (the children) spin bolas that are weighted by what look like representations of scales, and they (the children) are profoundly unchildlike and deeply uncanny. In a head-to-head, act-against-act I suppose I would pick Quidam's robotic head-tilting Diablo girls, but the two sequences are quite similar in that both make choices of choreography and direction that mechanise the performers and, as mentioned, give them a generally unsettling aura of aged creepiness—the bola boys in fact are brought onstage after two characters, looking for the princess, open a trapdoor and call into the depths, the children clambering up like an ancient evil never meant to awake.

For the Albert Hall run Varekai's clown duties were fulfilled by a man and woman playing the classic roles of bad magician and unglamorous assistant. It wasn't quite my cup of tea; I preferred a later section, featuring the bad magician, Steven Bishop, again, but this time in the role of a slimy cabaret singer whose heartfelt lip-synch of Ne Me Quitte Pas is interrupted by a spotlight that repeatedly cuts out and reappears, first just a step to the side but progressively further and further away, sending him running stage left to right, up the pole-trees, and finally careening through an open trapdoor.

There was nothing in Varekai quite to match the closing sequence of Quidam—though it has its own spectacular group finale using Russian Swings—but I think that Varekai probably hangs together a little better, overall, and has to its credit a suffusing atmosphere of benevolent weirdness that provides a little room to excuse the narrative fragmentation and design inconsistencies. Don't expect rigorous dramaturgy, deep thinking, or anything groundbreaking for the present day, and you can sit back and enjoy the show.