Monday: No Man Is An Island

~ Stockholm; Introducing CASCAS; Södra Teatern; The Story of Swedish Contemporary Circus; Manegen ~

On the whiteboard Kiki draws an incredible and super accurate map to explain: the districts of central Stockholm are spread over a chain of islands that lie over the wide river Norrström. There's mainland to the south, mainland to the north, but in-between are fourteen cloudlike drifts of land – named things like Kungsholmen (King's Island) and Långholmen (The Green Island) and Kungliga Djurgården (The Royal Game Park) – which are in fact just several among thousands in a great archipelago thrown west toward the country's sparely populated heart.

We are on the island Södermalm, in the theatre Södra Teatern, on I think the fourth or fifth floor, gathered at the warm interior of a small, bright meeting room with runs of windows on two sides. To the north is the river, in places frozen, and then the old town, where the domes and spires of broad, Lutheran churches appear over low buildings. The sky is a cold, even blue; to one side, the cut stencil of a daytime moon.

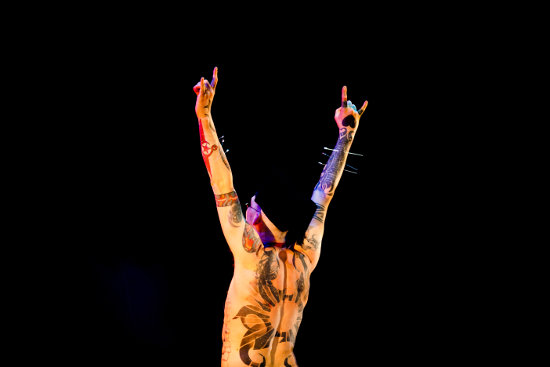

We've come to Sweden, ten of us, for CASCAS – an EU mobility project whose unusually clever acronym stands for Circus And Street Arts Come And See. Taken demographically we're a scrupulously diverse mix, from the UK, Spain, Belgium, Malta, Greece and Lithuania, with even numbers of men and women, and professional backgrounds that include a seasoned street artist and researcher, the founder and director of a contemporary circus, several heads of festivals / programmers / people working at development organisations, an aerialist and rigger, an actor and entrepreneur looking to start Malta's first contemporary circus1 – and me (a journalist, I suppose). Directing the project, our gracious hosts: Kiki Muukkonen, the artistic programming director at the multitasking creative centre Subtopia, and Christoph Fielder, also working for Subtopia, a slender and cool-seeming Swedish-American who has given much of his skin over to tattoos of butterflies – sized from a large portrait rendition on the dorsal thumb muscle of his right hand, down to tiny specimens pinned in the space between second knuckle and nail on each finger.2 (He looks as though he perhaps has shamanistic powers to control butterflies, directing them with gestures in great storms.)

This Swedish event is a kind of trial run – it hasn't happened before – but the official line is that CASCAS will:

Champion intercultural understanding and provide professionals in the fields of street art and circus the opportunity to explore different cultural contexts, share models of good practice, make new connections and challenge accepted wisdom.

Myself I have been framing it mostly to jealous peers as a 'free holiday', but, as Kiki hands around the sheets and lays it all down, the programme for our five-day tour of Swedish circus and street arts is revealed as an impressively engineered schedule of back-to-back visits to, and talks at, venues, training facilities and education centres that culminates in two days at Subcase, a professional showcase of Swedish circus held at some place called Hangaren.

Today though is a half day and after introductions among the group3 our first meeting is with Anders Ålander, the senior producer at this very venue, Södra Teatern. It's a strange sort of an institution, not quite analogous to anything in the UK but perhaps somewhere between Battersea Arts Centre and a West End theatre: they have an old-style, mid-size auditorium, red and gold, reached by a grand double stairway, but then also a live music space and bar that opens out onto a high terrace.4 Taking currently 70% of their revenue from sales and pushing (or being pushed) towards 100%, they bring in shows like La Clique to fund the work where they make a loss. They do music, performance, comedy. The venue is too busy and its running costs too high for it to act as a creation centre or to support the long-term development of work, but it's one of the bigger wheels in the machinery of a commercial theatre sector increasingly interested in the saleability of circus performance. Later on in the week, we will be coming back here to see Cirkus Cirkör, currently hoving into view of the end of a giant nine-week run of their new show Wear it like a crown.

Cirkus Cirkör: a name you might know, and, if you had to pick just one, by all accounts the defining influence on Swedish contemporary circus. On the plane over to Stockholm I read 'Fragments of the History of Contemporary Circus in Sweden 1990-2010', an article co-authored by Kiki and the researcher Camilla Damkjaer that uses interviews with six key figures to pull together a rough narrative of circus' ascendency as an artform – because if there's one thing that every CASCAS participant knows (or thinks they know) already it's that circus in Sweden has had a very fast development, and one of the major interests among the group, a running energy beneath every other curious question or point of interest, is why and how it has advanced at such a rate. We have all heard whispers of a mighty infrastructure and of custom-built training paradises shimmering on the outskirts of the city. Where has it all come from? The story that 'Fragments' assembles has many parts, and talks of the effect of incoming work from companies like Archaos, Circus Oz, Varieté Vaudevill, Cirque Plume and Cirque Ici – politically aware work, often character-based, usually aggressive and anarchic – as well as the foundation provided by Swedish practitioners doing 'new circus' before that was even a term – among them the street theatre group Jordcirkus and the vaudevillian troupe Gycklargruppen – but, still, the story of Cirkör is the spine that the others wrap around.

It starts in the early 90s with a young Swedish artist, Tilde Björfors, visiting Paris to work with Ariane Mnouchkine of Théâtre du Soleil. While there, she falls in love with the circus and is inspired to quit her work in theatre and to return to Stockholm to found a company of her own, Cirkör. They evolve quickly, changing the landscape around them: in 1994 they organise a circus festival at the venue Orionteatern; in 1995 give performances at Stockholm's Water Festival, where they meet and befriend members of Circus Oz; in 1997 start the country's first professional training programme, Cirkuspiloterna, in the cultural house Medborgarhuset; in 2002 expand their outreach work and move to Subtopia within Botkyrka Municipality; and in 2005 turn Cirkuspiloterna into a full-time accredited degree course partnered with the university Danshögskolan. By 2011 the company are enormous, running their degree programme, producing large-scale shows that tour around the world, working with 20,000 school children per year. Enormous.

Throughout their fifteen(ish)-year history, the company developed their artistic work. 'Fragments', or its group of interviewees, characterises Cirkör as drawing on the irreverent strategies of new circus, but in 2008 they performed Inside Out, a production that was both a big leap forward for them in terms of international profile and success, and, as I understand it, a departure from their usual style. And what I'm interested in, the thing that really I feel I'm here to seek out, is what stylistic trends, what methods, what hybrids are currently showing face in Swedish contemporary circus – and, then, where they originated. It feels that Cirkör may be the key.5

Following Anders the next speakers, and the last of this abbreviated day, are two board members from Manegen, an organisation set up to protect the rights and to lobby on behalf of Sweden's circus and street artists – one of them Ivar Heckscher, former director of Cirkuspiloterna, and the other Manne af Klintberg, a sporadically beatific and grandfatherly clown who looks like perhaps your favourite physics professor – bowtie, waistcoat and watch chain on display, deployed; esteemed white hair floating outwards in fine Van de Graaff strands.

What do Manegen do? At the moment, a little legal representation and advocacy – they give the example of leaning on a misbehaving festival to make them pay the money they owed an artist. And what is there for them to do? Seemingly everything. When first pulling the organisation together they arranged a meeting of 100 performers, out of which came 150 'wishes', from which Manegen, Ivar and Manne claim, has so far fulfilled two. It's a start.

They give me the impression that the Swedish scene has developed unevenly – so that even if there are incredible buildings and facilities, other things, like the legal protection Managen hopes to build, are lagging behind. Asked why certain elements of circus have advanced so far and so fast in the last few decades, Ivar (naturally) traces the development back to his former employer, Cirkör, crediting particularly Tilde as the figure who persuaded the regional government of Botkyrka to invest in Subtopia as a social project, but thinks ultimately that, whatever the leading edge of the movement, it was down to the audiences, and their receptiveness, or readiness, for a certain style of work: 'There are things that are pressed on the audience by government, and then there are things that come truly from public demand.'

Asked a similar question, but slanted more toward aesthetics, Manne sidesteps. There are new facilities and initiatives, new words even, but artistically not so much has changed, he says. The only difference is between the old humour, 'which is kind', and the new humour, 'which is like fuck off', and it's all, from his perspective at least, just more of the same: 'the new with new circus is the name'.

Tuesday: The Writing on the Pavement

~ The Frozen River; The Long Arm of Subtopia; Clowns Without Borders; Kulturhuset, The Water Festival & Stockholm Culture Festival; Street Marketing for a Street Festival ~

Early morning, -15°C, walking alone through the streets and squares of Stockholm. No one is going to work. Everything appears to be neat and regular. Along the fronts of sandy buildings I see a few windows that have been painted on, for symmetry. Yellow JCBs are out driving and piling snow in what appear to be not well-chosen positions, scraping down to reveal a bottom layer of ice that leaves cars spinning their wheels at the start of marginal inclines.

Between two buildings, two houses, I find a rail that protects a precipitous drop, staggered by narrow road-ledges but nonetheless some few hundred feet. Beneath, cutting into rock, long stairs lead down to the part-frozen Norrström where the idling engine of a cruise ship, Princess, agitates the water. Around the stern the water is the texture of oil paint; away there are clean white sheets of ice and darker shapes in huddles. To me it feels strange, and with about ten minutes before it's time to go back to the hotel and start the CASCAS day, I hurry down one set of stairs, then another, and hit a wider road, perhaps fifty feet above the river, where buildings obscure the view. I find a gap between two tenements and peer through.

Sitting on clusters of inland ice, the larger pieces of a drifting tessellated pattern, colonies of birds crouch into themselves; overhead a few fly, beautifully and asynchronously, in a thin cloud.

***

By the main entrance into Subtopia there's a giant, muscled arm, a glowing turquoise, that emerges from the snow as if the titan that owns it lies buried underneath – but if it weren't there then from the outside the complex would look like a school: a long drive, a wide courtyard, trees around the borders, boxy buildings; and everything quiet now at mid-morning, during lesson time. And in fact, in part, it is a school: Cirkus Cirkör are based here and run their Secondary school education programme (a three-year syllabus, something like a BTEC) as well as a professional training programme which began in 2000 as Cirkuspiloterna and then in 2005 was replaced by an accredited higher education degree managed by Dans- och cirkushögskolan (DOCH). Cirkör are the biggest resident, but Subtopia is a creative/cultural hub that houses some 50 other organisations and companies, all working within the arts, and most of them within circus or film.

Inside, Subtopia is red and white and clean-swept, with big high halls and colourful offices and little annex spaces where tired circus artists can catch 40 on plump velvety sofas. The whole thing is the size of perhaps a small campus university. The site is a run by its own administrative team, and we meet with managing director Karin Lekberg, who draws a large tree on the whiteboard of a meeting room to explain the various things that go on here. Boiled down then, Subtopia: offers mentoring/coaching to its resident and visiting artists – and (it seems, informally) to everyone else – in the form of advice on how to apply for funding, plus through the provision of technical and marketing support; organises a festival, Subtopiafestivalen, and a professional showcase, Subcase, in alternating years; offers residencies and opportunities for creation; and provides a space for a 'circus village' where Subtopians can park their caravans and live on-site. Their goal has been to create a place 'where creative people can feel at home'.6

The construction of the site was funded by Botkyrka Municipality, an outlying suburb of Stockholm considered by some a problem area, and in fact the Municipality owns the site – Subtopia rent the building and then in turn sublet it to resident companies with a 50% subsidy. It's extraordinary to think, and Karin, perhaps deliberately, skims over it a little, but the Subtopia Board is comprised mostly of local politicians...

Karin departs and Lars Wassrin and Mia Crusoe come in, respectively the head artistic producer and head of courses and training for Cirkus Cirkör. In their presentation there's not much that's new to me. Lars confirms the scale of the company's international touring and shows a slick and kinetic trailer of Inside Out with Irya Gmeyner belting out My Angel. Mia talks a little about their work in schools, explaining how they suprise the students with unannounced workshops – which, going on a little more video, are pitched very successfully at a level of raucous low humour. In telling the story of the professional training programme and its integration with DOCH, Mia reveals that the course, up until now split between the facilities at Subtopia (twenty minutes drive from central Stockholm) and DOCH's own centre in Östermalm (actual central Stockholm), will be moving entirely to DOCH, leaving the Subtopia training facilities freer for residencies and creation and youth work.

Without further ado former degree course student Viktor Gyllenberg7 takes us down to see the main Subtopia training space, and we hang around at the hardfloor edge, among the discarded shoes that wait for the return of their owners like fussing parents. We gaze in. Equipment is up – nice wooden rings, paged-back loops of rope – and the start of a tumble track connects with our entrance as though to use it might be your first act on coming into the hall. Like all of Subtopia it's very bright, very clean, high and warm. Most enviably, it's built for purpose: on an automatic function part of the floor can fold tidily away like a trick of the Bond villain's lair – except that instead of a shark tank underneath it's a huge crashmat. I would like to stay longer, but, like all the stopovers scheduled for our week, this is a flying visit, and Viktor soon ushers us out, pausing only to point out that the big mural on the wall to our right depicts a trapeze artist who is in an impossible position – caught in the second before she plummets to her death.

***

The Swedish way of dealing with ice and snow seems to be to just drive on over it, regardless, and the narrower and winding roads of island Stockholm are clogged and slow-moving as we travel to Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts to hear Pelle Hanæus talk about the course he leads, A Year of Physical Comedy, run in collaboration with the Swedish branch of Clowns Without Borders. Clowns Without Borders are a worldwide network of regional organisations, inspired by the Doctors Without Borders model, who send clowns to areas where people, and especially children, are isolated and suffering. They don't go to countries where the population are starving or where there is ongoing armed conflict – on the understanding that something else needs to be done there first – but often travel to refugee camps and areas stricken by natural disaster or war.

Once we've arrived and settled on the laid-out chairs and benches of a top-floor studio Pelle explains to us that the clowning is just a tool – 'a really good excuse for human connection [...] to make people feel they have been seen' – but, then, that the effectiveness of the tool will be proportional to the training and skill of the artists – because a fundamental part of being a good performer is, put simply, reaching your audience. As well, the borderless clowns rely on their training as they have little idea of what's going to be asked of them, from one performance to the next. The organisation's philosophy is to field clowns – agents – who are able to bootstrap a show in the most difficult circumstances: the expectation is that you should be ready in 50 minutes to do a show for between 50 and 5000 people. You have to be a very good clown, a crack clown, to not just meet the minimum objectives of a performance in these conditions but to actually, really fly. Pelle stops short of painting the picture so I do it myself: a band of supremely tough motherfuckers, choppered in, these elite and borderless clowns crossing countries and continents to visit, to rain down, storms of happiness on the downtrodden and the dispossessed.

Pelle introduces us to a few of his clowns in training, a young and vivid bunch, and we see presentations of the sort of work they'd perform in the field – including a particularly good clown double act where a compulsively loud and nosy cleaner constantly disrupts a haughty and besuited man (Sir John)'s preparations as he builds to a brilliantly sharp and composed piece of ring juggling. After, they sit down to take a few questions from the CASCAS delegation. The course students all have prior experience, as actors or as street performers or as clowns, and have joined to further or to reorient their practice. One of them happens to mention the fact that there aren't any tuition fees, and that the course, like all higher education in Sweden, is state subsidised. I know this already, but have such a fascination with the idea that I like to hear it as often as possible: education is free...

... if you're an EU citizen. As of January of this year those outside the European Union (or the EEC – the European Economic Community) bear the full brunt of the course costs, which Pelle gives hazily as in the range of 20,000-30,000 Euros as though no one has so far troubled him or his team to work out a figure exactly. This is the first year of the course, a trial, and while they would like to continue next year they at present have no guarantee that they will be able to. Perhaps though you wouldn't expect a new training programme to have won its future after just six weeks, and Pelle seems sanguine enough about it all. Later in the year the university will decide whether to keep the course or to change it, and in the meantime the staff and students are preparing for a trip to Rwanda to work in the field – in at the deep end from the start.8

***

Heading up the zagging escalators to the top floor of the Kulturhuset we see its many faces: a children's centre, a cinema, an exhibition and performance space, the home of several specialist libraries – something like the Royal Festival Hall in London or Paris' vaunted Pompidou Centre (which Kulturhuset in fact preceded by three years, opening in 1974). For ahwile half of it, the back half, was rented by the Swedish parliament, though it has since become an entirely public building. Its modernist design is striking, best described by the Kulturhuset's own publicity as like an 'open, seven-storey shelf unit, mounted on a solid concrete wall'. The front of the building, which is all glass, faces onto Sergels Torg, one of Stockholm's major squares and a hotspot for political activism. Kiki tells me that when a far-right party won parliamentary gains in 2010 the marches and protests convened here. Looking down on the area it's hard to imagine how they might all have fitted: the plaza is about 1/2 the size of Trafalgar Square.

But Sergels Torg has other uses, and in the fifth floor Café Panorama of Kulturhuset we meet Claes Karlsson, director of Kulturfestivalen (Stockholm Culture Festival), one of the few in Sweden to have a major outdoor component. Its precursor was The Water Festival (which Claes also programmed), an event that sprung up following the repeal of laws that forbade citizens to eat and drink on the streets of Stockholm – TWF being, as well as a festival of music and performance, a great thrashing orgy of outdoor eating and drinking that was, naturally, incredibly popular and drew vast incoming swathes of thirsty tourists. It got, the government felt, too big, too boozy, and when it was shut down Claes was tasked to replace it with a demotic civic event that would be more sober and decorous and not block off so many roads.

So Kulturfestivalen is 75% music, most of that in the nebulous category of world music, though it also programmes dance and performance and circus (in 2010, Race Horse Company, La Scabreuse, Cirkus Cirkör, Circo Ripopolo). The Water Festival used to programme circus too, bringing over Archaos and Cirque Plume and Circus Oz and giving Cirkör one of their first big breaks – for Claes it's been a long-term commitment and interest. In describing the changing attitudes of the government toward culture, and skirting around the issue of cuts and reduced funding, Claes says that one of the big shifts in attitude has been that politicians used to be quite snobbish about arts and tourism, but now tourism is accepted as a part of the festival, of every festival, and a high percentage of international audience members is a goal to be aspired to.

We go out then into the wicked night-time cold, the CASCAS participants from the warmer countries jumping up and down and eyeing Claes pointedly as he gestures to the empty plaza and explains where, during festival-time, activities take place. Sergels Torg reminds me of my old university concourse – it has a snazzier design, with an interlocking pattern of black and white triangles, but at base it's a concrete plaza surrounded by roads and crossed by an overpass. You wouldn't call it beautiful, but when voices started to call for the buildings of the square to be torn down and for Sergels Torg itself to be reconfigured as a grassy area with traditional wooden buildings it was the younger generation who objected, and pushed back, and eventually collapsed the movement.

***

Not very late night, but late enough night, in the empty dining antechamber of the Columbia Hotel, Thorsten Andreassen addresses a sleepy CASCAS group on the subject of Stockholm Street Festival. It had its first edition last year, in 2010, and Thorsten founded it out of frustration that there wasn't much out there for street artists in Sweden, and on the conviction that that couldn't be for lack of an audience. So with about 3000 Euros funding from the city plus a substantially larger sum of his own money he put together a small, three-day festival for Kungsträdgården Park.

The festival's marketing campaign grew vibrant and strange by the necessity of having no budget. Without explaining how (I would like to know how) Thorsten negotiated some truly leftfield sponsorship from a company that produces industrial cleaning equipment that uses high-pressure water – he and his team heading out onto the streets of Stockholm in the small hours with large stencils to blast the pavements. It turns out that they're so dirty that when you hose them down there's a subtle but clear contrast, and, happily, that the parts of the street with the highest human traffic, the ones where you most want your brand, are where the tarmac is the brownest and most disgusting. They soon discovered that the white bars of zebra crossings were the finest canvas, and when some passing policemen asked them what they were doing they said they were cleaning the streets, and the police stood around for a bit, then left.

Thorsten – who appears as a slightly ramshackle and absent-minded magician9 but who obviously hides some borderline demonic negotiation skills – also got sponsorship from a company who produce asphalt stickers, getting a free set impressed with the faces of the festival performers, ready to be laid-down on park walks in the SSF equivalent of the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Then there were the hats. Thorsten wanted to impress on audiences the tradition and responsibility of putting money in street performers' hats, and so a black felt detective hat became the symbol and brand of the festival, worked into a city-wide Find the Hat scavenger hunt that saw audience members scouring the city for these scarce, precious, hidden hats that would admit them to a draw of unusual prizes donated entirely by more generous and unlikely sponsors. By the end of the week preceding the festival the game had taken the city entirely in its grip, and Thorsten found people trailing him through the streets waiting for the moment to snatch the hat he was wearing.

It was all done on a shoestring. The festival drew crowds. Through the whole thing no one got paid except, on a point of principle, the artists.

Despite the late hour, everyone who runs a festival makes notes. Thorsten says he plans to bring back the Stockholm Street Festival in 2011, and hopefully expand it, but hearing him speak after Claes gives us a clear and unsettling view of the disparity between his own limited resources and that of a bankrolled festival like Kulturfestivalen, which – for all that it programmes good shows, supports artists, shores up the sector's ecosystem – is probably sold to its funders as a branding exercise for the city and country, and explained in terms of the revenue it generates from tourism. Thorsten is the first person we've met who, clearly, is putting a lot on the line – really his whole livelihood – only for the sake of artists and for changing things for the better.

Wednesday: We Insist Strong Positions

~ The Old Town; DOCH; Where Is Swedish Power; The State of the State; Orionteatern ~

In the Old Town narrow streets and tall buildings create canyon alleyways, four stories high. Workmen are on the edges of the roofs with bright plastic shovels, throwing down snow that separates and thins and arrives at the ground as a dusting like icing sugar – clean white against the trodden-in brown of the pavements. A man on the ground with a flashing silver whistle starts and stops the work to let pedestrians by.

Some of the walls have these lengths of pliable red plastic that have been bent into semi-circles and attached at preprepared points, creating forbidden zones that ward people from falls of snow and ice. Walking by a church, there's a drain outlet where running water has fused into a great jagged spear: heavy ordinance.10

***

Grey and steely, long corridors, many rooms – Dans- och cirkushögskolan, The University of Dance and Circus. Our retinue of fifteen or so is led around the building, in one room casting our eyes on a sheepish wirewalker, seeming to push him off balance by the force of our collective attention; moving through a slender, unfurnished studio where burly men in only shorts practice transitions from one-arm handstands; looking down from a tech room on a group of dancers debating a subject which dissolves in the distance of our observation.

We trail then into a lecture hall to hear from Marie-Andrée Robitaille, the artistic director of the university's circus programme, a former artist with Cirkus Cirkör, and a former talent scout for Cirque du Soleil, and from Efva Lilja, vice chancellor at the university, an established choreographer/dancer, an impassioned and eloquent defender of the enriching and immeasurable benefits of cross-cultural collaboration, and a steady critic of the Swedish government's recent emphasis on the 'cultural industries' interpretation of the arts. Between them they explain that the course here started in 2005, that just seventeen students are taken on every two years for the BA circus programme, and that there are only 200 students in the whole university. The course is once again free for EU citizens, but if you're outside the EU it comes in at a staggering £50,000 p/a and you might as well build your own circus training centre. To offset the resulting Eurocentricity the school invites teachers from abroad and brings in students by the backdoor of exchange programmes. They can also invite artists to be professors, respecting a practical rather than academic background, as one of the USPs of the Stockholm school is its commitment to the emerging field of artistic research.11 It's possible to go through the whole higher education trajectory, from BA to MA to PhD, purely through practice, with no theory, and currently the university has three research doctorates who are practicing artists assessed on their artistic work: John-Paul Zaccarini, Tilde Björfors and Åsa Johannisson.

Efva tells us that despite their recent growth, the circus arts have no label, no official recognition, within the Swedish funding system; dance didn't even get there until 1997. But, she says, DOCH aims to be forward-looking, and to train students not for the short-term pressures of a government fixated on the potential economic benefits of the arts, but to train them instead as artists who will influence and shape the future: 'we don't advocate for what is, we advocate for what will come'.

***

Hefting a directory-size 2006 research paper covering Sweden's cultural industries, Tove Sahlin and her colleagues at WISP (Women In Swedish Performing Arts, though they're open to other acronym interpretations) explain that the country maybe isn't as socially enlightened and liberal as its citizens like to tell themselves, and that their 'belief that we are equal already' is misplaced and dangerous. As the 2006 research brick shows, the situation in Sweden is the same as the UK: in total there are many more women then men in the arts and creative industries, but, still, many more men than women in the highest positions.

In drawing attention to this imbalance, WISP act as an advocacy group who seek to exert pressure through creative practice – they aim to make work that interrogates gender inequality and power structures, and their meetings are open to all members (they have 800-1000) and run on a system that reconfigures Open Space as Open Art.

Our discussion is Open as well, twenty or so of us at a big table, and in the course of its meandering progress it happens to emerge that of the most recent batch of seventeen students joining DOCH's BA circus programme sixteen were men. The conversation breaks into little eddies debating whether the university's strict policy of selection on merit is the appropriate choice, or whether it creates a social and psychological barrier to entry. It's inflammatory stuff – whatever side you stand on it's hard to be indifferent about positive discrimination – and the room is engaged and abuzz when WISP depart and the next speaker comes round: Elin Norquist, a representative of the Swedish Arts Council.

She is, perhaps in keeping with all Arts Council employees in all countries everywhere, cautious in volunteering information, answering questions politely and with little personal animation – a dry and professional spokesperson. But she does give us a clear picture of how things work, and the first big difference between Sweden and the UK is that the SAC doesn't have the same formal (if nominal) separation from government as the UK body, and in fact it explicitly exists to carry out government policy – if you visit their website the very first sentence tells you that this is so. National institutions are directly funded by the government and regional independent bodies are funded by the SAC. Regionally it is politicians who decide on applications and funding. 50% of the total national budget goes to just seven big institutions (the opera house among them, as you'd expect).

Circus applications fall into either theatre or dance, and circus has no category of its own. That's the case in the UK too of course, and you might ask, Why does it matter? Well, last year there were six or eight (there's a little uncertainty) applications from circus companies out of a total of around 150 – a low number considering that there are something like 200 contemporary circus artists and 45-50 companies in the country – and one explanation is that circus artists don't think they're eligible, or that it's a waste of time to apply. After the WISP discussion everyone's thoughts and attention are sharply focused on the politics of selection, categorisation, language – and we know from conversations earlier in the week that it's not uncommon for circus artists to identify their work as anything but circus for the sake of marketability. Crosstalk begins to cut over the table; Elin sits neatly and watches.

The CASCAS group are starting to get restless, starting to form opinions, and the final revelation of the meeting, a casual aside from Kiki, is that if a right-wing government is elected in Botkyrka then Subtopia runs the risk of being sold to private interests – that this is in fact an electoral pledge of the opposition group.12 With that, the meeting disperses.

***

In a back room they're busy taking out parts of the ceiling to increase the light to regulation levels for the six horses that'll shortly be stabled here. We're in Orionteatern, back on good old Södermalm, looking around a building that used to operate as a machine workshop producing railway equipment. It's been converted a little, in the sense that there are seats now and no remaining machines, but you could otherwise imagine that the industrial activity stopped only yesterday – there's dust on the floor, and bits of metal and wood in piles, and coils and stacks and buckets of that particular quality of stuff that you get in garages and workshops only. The main hall, off which the horses are to be kept, is ten metres high, with wood standing-balconies about a third of the way up that give it, for me anyway, the feel of some old Elizabethan theatre like the Globe.

The venue's remit is experimental and non-traditional performance and it has a long-standing relationship with circus, having programmed in the past such luminaries as James Thiérrée and Le Cirque Invisible. These last six years it has also hosted the cabaret variety night Salong Giraff, and we meet two of the Salong organisers, Viktoria Dalborg and Erik Åberg, who sing the praises of Orionteatern as a space to do, more or less, whatever they want with their Salong.13 When asked where circus will go next and what its future might hold though they say that what the artform needs, alongside formal recognition from the government, is funding for circus-specific venues and centres. There are pockets of activity now, and things are growing, but for dedicated venues there's only one – Hangaren, in Subtopia, where we're going tomorrow.

Thursday: Property of the Crown

~ Hangaren; No Expense Spared; Poetry in Motion; A Walk in the Graveyard ~

I was told that the Palace is empty, uninhabited. The King has another residence, and the hundreds of rooms here are in stasis. Looking through the open gate to the courtyard outside there are two royal guards, wearing traditional – therefore ridiculous – navy and white uniforms with spiked helmets and tassel shoulderpads. Suddenly, as though someone has turned a key in his back, one guard cranks out a ten-foot forward-march, stops, wheels around and returns.

There are no signs anywhere indicating the Palace is public; I am nervous to approach. It seems like this man probably has a very small number of permitted actions and interactions, and that it's possible, even likely, that a trespasser on royal grounds is ordinarily shot on sight.

So I watch from a distance. To keep away birds, netting flows down the front of the Palace, moving in a small rippling wind as though the building is breathing in its sleep.

***

I think they used to store wood here, but it's long enough to build an aircraft, or to house trains, divided now by black curtains to create three spaces each so big and so high that they have layers of lighting: fluorescent bars affixed to the faraway slopes of the roof, then wood Ts of softer yellow bulbs suspended from wires as though the last remaining trace of a removed ceiling. It makes me think of a Peter Carey short story about an architect who builds a dome so large it generates its own weather system. In one corner, like an art exhibit honoured by the emptiness around it, there's a stationary wooden wagon, an orange-red lampshade glowing at the window to create the fiction that somebody might be home. A great cable reel stands nearby, painted with a star, further down there are iron garden chairs and tables,14 low cute golf fencing entwined with fairy lights; otherwise just [echoing voice:] space, space, space, space.15

It's Day 1 of Subcase, the showcase of Swedish circus organised by Subtopia and held here in their own Hangaren, a new venue for performance and creation that was opened in 2010 with the first edition of Subtopiafestivalen. Hangaren is 2300m2, high enough for any circus discipline you care to practice, big enough by far for any circus company currently making work. Inside its purpose is clear, but if you walk around the exterior structure it feels a little like a sinister walk thorough a forbidden compound – the steel shell is blank, mostly unwindowed, at the centre of a fenced-in area sited in a fairly remote part of the suburbs.16 It's just one of those buildings that you see, that you perhaps drive past, and think, What goes on in there?

***

Fish is first, a show directed by Åsa Johannisson, one of the PhD students working at DOCH. It's actually a stage adaptation of a film (also by Åsa) about a lonely woman who meets a zookeeper. It feels very old-fashioned, soundtracking its emotional moments with cartoon effects, characterising its two protagonists as twitchy ur-clowns, and senselessly mixing the metaphoric and representational qualities of its mime (lots of people crossing invisible boundaries that moments ago were an impassable wall). As a show 'about loneliness' it's hard to see whose experience of isolation or marginalisation it could ever speak to, and it uses circus skills in that pedestrian way where the Chinese pole is a lamp post or drainpipe and the slackwire is a washing line. The CASCAS block sort of exchange glances and after there's a certain amount of scandalised whispering as the amount of funding given to Åsa, 1.5 million Euros, is passed around. That amount was actually for a long research project, Beyond and Within, that incorporates the Fish film plus a larger show devised inside a glass-blowing workshop/factory, but still: it rankles.

Immediately following Fish is Poetry in Motion's Undermän, a smart and genuine and quite touching piece that draws together the stories of three bases who've lost their (romantic and performing) partners. It's in that style of performance that favours realness – the performers are themselves on stage, and the stories are their own, without a great deal of abstraction. In my notebook after I draw a picture of one performer's glasses, which struck me at the time as key.

It turns out to be the high point of the Thursday Subcase, and, after a conceptually leaden and earnestly emotive piece about gendered abuse, an overrunning schedule pulls us away from three works-in-progress and back into town, to Södra Teatern, for the last show of the day, Cirkus Cirkör's Wear it like a crown.

I think a lot of things, watching it, but the main impression, which seems to be shared among the CASCAS group, is of a production that is stylishly executed and well performed but very bland, both in its message of wearing your fears and past failures with pride, and in adopting a smooth and frictionless aesthetic that sands down the personalities of the performers themselves for the sake of ease – it will never upset the passively of your spectation. In the 'Fragments' essay, Tilde, both the artistic director of Cirkör and the director of this particular piece, says that in the early 90s Cirque du Soleil was 'far from what the artists gathering in Sweden were reaching for'. Maybe then it was true, but in Wear it like a crown (and in the last show Inside Out) Cirkör exhibit the same signs as CDS of a commercialised practice that, even as it grows in size and success, is artistically reduced and delimited by the suffocating needs of the market. And just as Cirque du Soleil do, they retain like some dessicated fetish a memory of their former ambitions, framing their shows in intellectual and often cod-scientific terms – in the case of Wear it like a crown, neuroscience – without allowing the research to play its full role in shaping the final show, without making the piece truly a conversation with its topic.

As it ends, pushing through the twin streams of audience members crawling down the Teatern's grand stairway, I skip out for a lonely walk through the nearby graveyard. The church is wide and curvaceous, yellow and white, its windows round or nearly round, fitted with plain glass. I take the diagonal paths, going back on myself to draw a cross, and think about entertainment and captivity, and about hunger and nourishment, and think whether it can possibly be true that the more people you speak to the less you can say – and then let it all slip out of mind. People have put out candles and lanterns before some of the graves. Lamp posts refract their lights into attentive stars. I walk for twenty minutes, listening to the sound the snow makes as it compacts underfoot, trying to think what word could describe it.

Friday: No Man Is An Island (Reprise)

~ Marie-Louise Masreliez; Burnt Out Punks; 2 Funny; Pain Solution; Objectify ~

Instead of walking this morning, I meet with the director Marie-Louise Masreliez, whose work What About Charlotte I watched a few weeks ago on DVD – a piece, like Undermän, built from the personal stories of the performers, but, entirely unlike Undermän, one that distils those stories until their details and specificities are unrecognisable. For the spectator it's strange and quite solemn, a bit like something has been unearthed and you're watching it being examined, wrapped up, and re-interred.

So we do an interview in a charming café that's three minutes walk from the hotel but which alone I would never have found, and towards the end I try to goad Marie-Louise into saying something rude about Cirkör – or at least into setting her own practice against theirs. But she doesn't take it that way, as an aesthetic question, and says instead that it doesn't matter whether it's to her tastes or not; right now in Swedish circus 'every little thing that happens feels like a victory'.

***

Back in Hangaren, mid-morning, for three presentations of works-in-progress. One is a short showing of the piece Hello!, which (to English eyes) looks like it has been influenced by the Forced Entertainment devising style (though equally likely its in response to some parallel Scandinavian practitioners). Another is two circus artists / dancers showing a little video as a creative impetus for a work they hope to make. The last is from a company called Burnt Out Punks. They seem like nice guys, but also like they came up with their presentation and pitch the night before, at maybe around 3am, and manage to communicate that (a) they like fire and explosions, (b) they want to take it to the next level with bigger fires and louder explosions, (c) they have had an idea to make a show that is about the Stockholm syndrome, with the aim of inducing the syndrome – i.e. a warping and sometimes permanent mental disorder where a baseless and illusory empathy becomes the only shield against the extreme stress of imminent violence – in the audience. They get some applause.

Following the presentations there's a full-length piece, 2 Funny: The Show, by John-Henry Larsson and Rasmus Wurm, who are perhaps not at their best performing in English, though their particular style of variety comedy and weak jokes and audience interaction17 is anyway probably tailored for an audience considerably drunker and less coldly judgemental than the Subcase delegates, who I spend most of the 2 Funny set imagining as a flock of evil bats watching upside down and with red eyes. But whatever – I'm one of them, and sit stonily throughout the performance (though I have to admit that, in a roundabout way, John-Henry gave me the biggest laugh of the week18).

Next it's a show called Pain Solution Sideshow, by a company called Pain Solution (who I think would perhaps prefer to have their name written in capital letters, PAIN SOLUTION), a troupe doing fakir stunts in the Circus of Horrors / Torture Garden line rather than in the honouring the deep religious/spiritual roots of the practice line. They bang nails through their noses, drink poison, lie on beds of nails, mount (for the finale) a giant hook for a terrible piece of aerial, but this sort of thing got overtaken by live art a long time ago – that's where the real innovation in blood-letting and shocking penetration and self-induced vomiting is.19 A front row audience that in the semi-dark I am pretty sure are members of Burnt Out Punks cheer them on, and the woman behind me keeps rolling an r in a really weird and quite piercing but I suppose appreciative ululation – still, it's probably safe to say that the piece falls outside the range of most Subcase delegates' interests.

So then the last of the day, the last of Sweden: Jay Gilligan, a sometime associate of and performer with Cirkus Cirkör, but here a solo artist presenting his own piece, Objectify. As we file in, he stands by the entrance and says hello to each of us, which I'm always a bit wary of as a theatrical strategy, and here it's about the easiest and most direct performer/audience connection of the evening. Jay delivers a piece that if you're a juggler you might be able to read as the history of modern juggling, but which to uninitiated eyes is structured opaquely. The music might be procedurally generated or microtonal or some other synthy thing – I haven't the slightest idea. Jay has a couple of magic light boxes that he presses and this configures a flashing grid that somehow generates complex digital music. There's a good deal of laptop noodling, no speech, not much eye contact, the manual turning off and on of stage lights. Afterward more or less everyone in the CASCAS group criticises its way of looking inward and its apparently low valuation of the importance of the audience's attention and presence – but I don't know. I think that actually it's the kind of show that needs the audience's attention and involvement above all else; it's difficult, and you have to concentrate, but only because Jay hasn't, beforehand, done all the thinking for you.

Saturday: I Came, I Saw, I...

~ The End ~

Sunlight here is a visual effect, an illusion, a trick that carries no sensation to the skin. Turning into a street running across the angle of the rising sun, the pavement walk is shadowed and light cuts a crisp line below the windows of the fourth floor. Turning again, another angle, and sun floods in and kicks on the snow and ice like shattering glass.

Outside the Swedish parliament, on a bridge over fast water, there's broken ice like torn paper, and transparent shapes near melted away. Two male ducks. Steam off the river scuds low and vaporous.

***

Kiki tell us that last night she had a dream that CASCAS was a verb, and that in the dream the exact definition was, perhaps, unsure. Sitting on the balcony of an old and (at this exact moment) unused cinema we're running through an evaluation of the week. Everyone writes down three words that they feel sum up their experience of the tour, and then we talk in turn about what it has made us think and about our general impressions. Everyone is grateful to have been invited, of course, and complimentary, of course, and this is expressed in some very eloquent and sincere ways.

When it's my turn, and as always happens, I mumble something that doesn't get close to what I want to say, though I know what I want to say, sort of: that it's been a privilege to meet the individuals that are giving so much of themselves in driving the development of the artform; that in coming to look closer at Sweden you simultaneously receive a wider, and sometimes shocking, perspective on the activity of your own country; that the snow and ice and different buildings and other language has an influence and meaning that does its own subtle work; that even if you don't work a connection, partner with a festival director you have met, or programme an artist, the tracing lines of a network run beneath and outside of what is immediately visible; that I admired so much of what I saw, and that I want to be active, and to engage; and, finally, that the CASCAS week came at a time for me when I felt especially low about being a journalist, and it lifted me back up.

Naturally in the course of the roundtable people give their opinions of the strengths and weaknesses of the Swedish system, and there's consistently an observation that the quality of the artistic work in Sweden is low in the light of the artform's mighty infrastructure. I don't dare to talk about it all here, caught dumb between the temptation to act as though my outsider position grants a (brutal and iconoclastic) insight, and then the awareness that any judgement I can make is based on the shallow understanding provided by a brief visit. What I feel is that some of the in-progress work that the group criticise as bad is actually only young, and that it has the signs of newness: affectation of style and gesture; undigested artistic influence; early thinking. These are all good signs, as you need only a little imagination to read that there are artists interested in developing their own style, interested in the work of those that have gone before, interested in thinking.

The discussion is short, curtailed by the imminent business of catching planes and making connections. I'm one of the ones that have a little more time, and as the others load into the taxi, Kiki points out the location of the cinema and traces a line to the hotel on my ragged map (which is about to split into quarters ready to be buried to conceal the location of treasure). How long will it take, I ask. About twenty minutes, says Kiki.

Actually it takes more than an hour, following the river from the north-west of Södermalm, past the former prison-island Långholmen, along jetties and through suburbs with families and children in bright puffy coats with mittens tied on. The unfinished evaluation is still rattling around my head. Right now it feels as though Sweden is maybe a chapter ahead of the UK in the same story – that there are these great educational structures and dedicated spaces (even if they say not enough), but what's missing, as in the UK, is the funding or the paid work that allows graduates to progress beyond their formation and to live as artists. It's sort of a question of personal sustainability. At a discussion I was at once an academic said that circus is a young person's artform – for the young, by the young. Well, no. No. Working yourself down to a thin abraded wisp for the sake of a subsistence wage and the dream of something better is a young person's game. Perhaps a certain style of virtuosic and skill-based performance becomes harder as well – but you can make different work as your body changes, it might even be better, and if artists don't see that as an option it has more to do with the financial difficulties and the lack of precedent than the bullshit impossibility of the artistic challenges it presents. If you make it possible to have a career, really a career, then maybe people will stick around and continue making work instead of moving into teaching or drifting out of the sector altogether.

What happens otherwise is the companies who survive are the ones who choose to adapt their practice for corporate and commercial lines – as, at least in their production work, Cirkör appear to have done. There are advantages in having a successful organisation acting as a parent and hub in their region – you can make a huge list of what Cirque du Soleil have done for Montreal – and one with the means to support new work with the potential to outstrip their own, but they also shape the sector, and particularly public perception of what circus is and where its limits might lie.

There's a danger then that for funders and politicians looking into the artform – idly and askance, as though into a fishtank – it presents itself as the narrative of success: a company or an institution that supports itself, in good part, through commercial practice and partnership. Why doesn't everyone do that? Dependency on a politically-directed body that even in a liberal government is looking to hand the arts away has its dangers as well, but I don't know. From the outside, even if it ultimately fucks you over, state involvement doesn't seem to have the same erosive effect on an organisation's origins and heart as the creeping black tendrils of corporate entanglement, and there's at least some leverage in the form of advocacy and lobbying, or, failing that, democratic election.

Cirkör's rise has, more or less, been the narrative of Swedish contemporary circus as we've seen it reflected in the eyes of Ivar, Karin, Lars and Claes – so what's next? And what's beneath what's now? Undermän is a sign of something else, and I have this feeling that there must be work out there that's finding its own way, aesthetically, but don't know where it lives. From the outside, I want to see someone kick against the status quo; from the inside I think it's much more complicated. Poetry in Motion developed their piece partly through the support of Cirkör Lab; many of Sweden's artists have been trained on the degree programme the company began.

It seems as though Swedish contemporary circus has run far and fast in the last fifteen years, but that it has reached a critical stage in its development just as hard times bring the risk of harder politics. What's past is prologue, as they say. Now what?

Notes

1 Chris Dingli, an optimistic man and good company. You can read about his project here, perhaps turning a slightly sceptical eye to things that are 'under wraps' or project details that 'cannot be given away'; what the article doesn't say though, which is really the sort of trump card, is that the Maltese government have expressed a specific interest in developing a contemporary circus and are backing Chris as the man to make it happen. Chris was, in a good way, fairly pummelled with information in the course of the CASCAS tour: whenever he gave the brief précis of his project suggestions and advice came from all directions – for funding he could apply for, partnerships he could forge, existing Maltese venues he and his band of circus artists could attack and overrun. If he acts on even half of it then expect Malta to knock ageing France from the throne of contemporary circus in a few short years.

2 Also, (1) wrapping about one-third the circumference of his neck, written cursive, the words Expect Resistance, with Expect that murky tattoo-blue and Resistance a low red; (2) a bracelet of tiny vertical dashes circling his right wrist; and then (3), in the vulnerable divot between shoulder and neck, what looks the couple of times I sort of see it like a warthog with a Venus symbol for a face/head.

In my efforts to fully and secretly inventory Christoph's tattoos I am through the week frustrated by another cursive script tatt that runs below his collarbone – I see only the very top, the high arms of ls and ts riding over the hem of his shirt like the masts of a ship obscured by landscape. Despite a certain amount of disguised craning during discussions and standing up one time to pretend to go to the toilet I still don't know what it says.

3 I'm making a decision here not to characterise the individual CASCAS participants (with the exception of the odd compulsive footnote) – because as you will eventually see, and perhaps through tears of frustration, this article is already a test to patience/interest/eyesight. (Also though, crucially, because I'm quite likely to reencounter some of them in the future.) If you need a mental image then I'd recommend that whenever the group is mentioned you imagine the shuffling, robed hunchbacks from Dark Crystal. Why not, eh?

4 With the same view, or viewpoint, btw, that provides the sweeping introduction to August Strindberg's The Red Room.

5 Despite its title and numerous in-text references to its inadequacy/incompleteness, the 'Fragments' essay is an engaging read that follows a very interesting structure as a six-point discursive history, and has, obviously, rather a lot more to it than I've indicated above. The six interviewees, if you're interested, are Claes Karlsson, Tilde Björfors, P. Nalle Laanela, Seved Bornehed, Thorsten Andreassen and Ivar Heckscher (three of whom we met as part of the CASCAS trip). And if you're even more interested then the 'Fragments' article will be published as part of a book on Nordic contemporary circus later in the year. Watch for it.

6 The short of it is that Subtopia's pretty cool. My perception of the whole operation is that it's one of those organisations that has the wit and flexibility and imagination to equal the artforms it serves, and my second perception, if you'd like another, is that organisations possessing this quality are much more common in instances where they share a building with the artists who, in the end, they exist for.

7 So OK, a footnote for Viktor. Viktor, a native Swede, actually applied through the CASCAS programme to visit another country (there are tours later in the year to Belgium, Finland and the UK), but was unsuccessful. So the Swedish CASCAS organisers, bending the rules in what I would maintain was an admirable and perhaps characteristic way, tagged him onto the Swedish tour, and he was with us the whole week, half in the role of a person interested in finding out about the structure and systems of the sector (like us), and half in the role of a knowledgeable and experienced practitioner who was available for us to interrogate. Viktor is one of those unnervingly fluent Swedish English speakers, conversationally delivering elegant, looping sentences that make you feel like your relationship with your own language – your first language – has degraded to a point of absolute shame.

8 If you're interested in their activities there, then you can – should – must! – take a look at Pelle's blog, home to gorgeous-syntax prose like this: 'I didn’t know volcanoes glow in the dark, but crossing the bumpy lake Kiwu, on our way home from the prison island Iwawa, the pinkish cloud above the summit navigated us back to Gisenyi town. It rained, but the old passenger boat had a wooden roof. Water splashed from the side in our faces, and I lent a pair of warm socks to the youngest of the acrobats girls – a bit worried by the crossing, but courageous – for them to wipe their faces with, sock on hand.'

9 He is a magician, just to be clear.

10 Tuesday night, on the way to eat somewhere, walking over the lumpen, sliding pavements our retinue passes a chunk of ice that's about the size of a breadbin. Where did this come from? From the roof, says Christoph, and at first no one believes him, but he insists, and tells us that last winter a man was killed by a falling icicle, and it's like he's flipped some psychic switch. Now we approach an outhouse building and the depending fangs of ice – so many of them, ranked – have all the dark and terrible menace of a brace of hunting knives set on the wall of an isolated woodland cabin. I look at them closely – closely. The light of streetlamps jumps inside the ice and wheels and glints as we walk past, appearing to turn, looking right back.

11 Efva gave us all copies of three articles that I chewed through that night and the next morning. Two were not uninteresting but slightly stodgy articles by Henk Borgdoff, and the third was a wonderful essay by Efva herself that colocates the spirit of artistic research within her triple-function as an artist, a professor, and a vice chancellor. You can read it here.

12 One of the CASCAS participants pointed out here that perhaps, aside from 'consolidation', this is the reason that DOCH want to remove the circus programme from Subtopia and fully install it within their own facilities.

13 Afterward Viktoria told me that what they want to do next, and are in the process of doing right now, is dismantle the Salong and from its constituent parts assemble Kompani Giraff, with the intention of developing 'other forms of circus, variety and moving stage art'.

14 Weirdly islanded in the huge space, like a remnant of memory in a psychic void, I thought.

15 I spent a certain amount of Thursday's brainpower trying to think up scale analogies for Hangaren, but just kept imagining a 50s film where one biplane chases another into a building and out the other end. Tracer rounds peel back the metal of a wall.

16 There was a big block of time for lunch and networking and promoter/artist speed dating on the Friday at Hangaren, and because by that time I was beginning to get wracking, terrible People Fatigue I opted instead to walk outside in the deep, deep cold, around Hangaren's enormous footprint and out to the back, where there were hills and dark trees and rivers of snow. I spent a few minutes there, staring out through the reticulated mesh of a high fence, thinking that there's a certain kind of landscape that seems always to be waiting for you.

17 You can get an idea watching this video of John-Henry Larsson on what I guess is a Sweden's Got Talent type show.

18 Apparently I picked up a piece of their promotional material without looking at it, then emptied it out of my pocket onto my hotel desk and forgot that I had done so – coming back one afternoon to discover a condom in a cardboard sleeve that depicted a Swedish boyband, the 'Rolandz', decked out in opulent turquoise silk-suits. It took me several days and a discreet conversation with another CASCAS participant to establish that this wasn't a complimentary service of the hotel and to trace it back to its source – in the end Googling the Rolandz and finding the alluring, sexy song (/pre-coital anthem) the packaging recommends.

19 I don't want to be the jaded consumer of pain solutions, or to suggest in any way that the company should 'up their game', but watching someone push a long needle through the outer skin of their forearm just doesn't do anything to me.